Image source, SPL

Image source, SPL

By Fergus Walsh

Medical editor

In a world first, medical regulators in the UK have approved a gene therapy that aims to cure two blood disorders.

The treatment for sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia is the first to be licensed using the gene-editing tool known as Crispr, for which its discoverers were awarded the Nobel prize in 2020.

This is a revolutionary advance for two inherited blood conditions, both triggered by errors in the gene for haemoglobin.

People with sickle cell disease produce unusually shaped red blood cells that can cause problems because they do not live as long as healthy blood cells and can block blood vessels, causing pain and life-threatening infections.

People with beta thalassaemia do not produce enough haemoglobin, which is used by red blood cells to carry oxygen around the body. Patients with beta thalassemia often need a blood transfusion every few weeks of their lives.

How it works

DNA is the blueprint of life - and genes contain the instructions for how every cell in our body works.

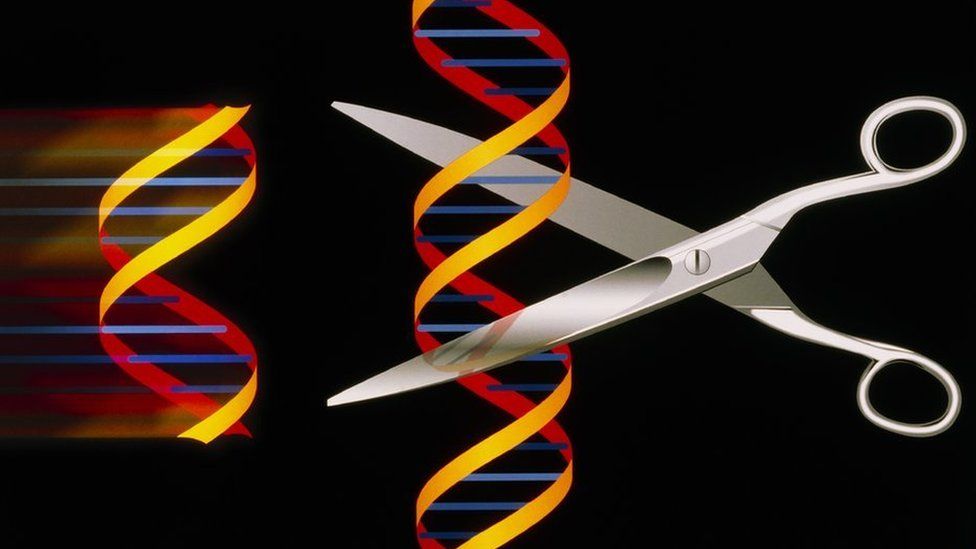

Gene-editing allows the precise manipulation of DNA. The treatment involves removing stem cells from a patient's bone marrow.

In a laboratory, the gene-editing tool Crispr uses molecular scissors to make precise cuts in the DNA of the cells, thus disabling the faulty gene. The modified cells are infused back, allowing the body to start producing functioning haemoglobin.

In trials, 28 out of 29 sickle cell patients were free of severe pain and 39 of 42 beta thalassemia patients no longer needed blood transfusions for at least a year. It's hoped it could be a permanent fix.

Trials are continuing in the UK, US, France, Germany and Italy.

Around 15,000 people in the UK have sickle cell disorder, most with an African or Caribbean family background. More than 1,000 people in the UK are affected by thalassemia, mainly those of Mediterranean, southeast Asian and Middle Eastern origin.

"Both sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia are painful, life-long conditions that in some cases can be fatal," said Julian Beach, interim executive director of healthcare quality and access at the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

"To date, a bone marrow transplant - which must come from a closely matched donor and carries a risk of rejection - has been the only permanent treatment option."

But now a "first-of-its-kind" gene-editing treatment called Casgevy has been authorised by the MHRA, he said.

In trials, it has been "found to restore healthy haemoglobin production in the majority of participants with sickle-cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassaemia, relieving the symptoms of disease", he said.

'I feel reborn after pioneering treatment'

Image source, Jimi Olaghere

Jimi Olaghere thought he would have to wait decades to be freed from his sickle cell disease - but he spoke to BBC News in 2022 after becoming one of the first seven sickle cell patients to have benefited from the revolutionary new gene-editing treatment in the US.

"It's like being born again," said Jimi. He spoke of how he felt it had changed his life. "When I look back, it's like, 'Wow, I can't believe I lived with that.'"

Jimi had lived with sickle cell since childhood. "You always have to be in a war mindset, knowing that your days are going to be filled with challenges."

John James OBE, Chief Executive of the Sickle Cell Society said: "Sickle cell disorder is an incredibly debilitating condition, causing significant pain for the people who live it and potentially leading to early mortality.

"There are limited medicines currently available to patients, so I welcome today's news that a new treatment has been judged safe and effective, which has the potential to significantly improve the quality of life for so many."

No price has yet been set for Casgevy, but the one off treatment might cost £1 million or more - which could be deemed too high a price for the NHS to bear.

For Casgevy, the drug is a personalised one-off treatment made from tweaking the patient's own cells - that makes it expensive and time-consuming. Add in the cost of research and development - there are just two labs one in the US and the other in the UK - currently producing the drug.

The Boston-based pharma company involved, Vertex, will want its product used as widely as possible so will need to set a price that health services here and abroad are prepared to pay.

(1).png)

1 year ago

17

1 year ago

17