Near the shores of the Barents Sea in Russia’s far northwest lies Murmansk, the world's largest city beyond the Arctic Circle and a popular destination for tourists hoping to witness the Northern Lights.

In the heart of the city, Murmansk Commercial Seaport carries out coal transshipment out in the open — sending coal dust into the air in a radius of several kilometers.

“When you stroll through the city center, when you take tourists there, everyone sees this coal dust," Daria, a local tour guide born and raised in Murmansk, told The Moscow Times.

At her job in the local tourism sector, Daria often shows guests her hometown’s iconic landmarks, like the monument to those who defended the Soviet Arctic during World War II, which are "all covered in coal dust."

"This certainly raises questions not just among Murmansk residents, but among guests from other regions as well — ‘What is actually going on here?’ And they often ask if it's dangerous to breathe this dust," Daria said.

Daria withheld her last name due to the potential risks of speaking to a media outlet labeled a “foreign agent” by Russia.

A persistent problem for over a decade, the effects of coal dust pollution have become especially visible in recent months, said Daria. Residents’ complaints about coal dust have surged fifteenfold compared to last year, Governor Andrei Chibis said in March.

Beyond its unpleasant appearance and harmful impacts on public health, this coal dust is a sign of the port's expanding activity as Russia pivots its coal exports from Europe to Asia under wartime sanctions.

After Chibis called on state prosecutors to investigate Murmansk seaport for potential violations, port management acknowledged in early March the need to enhance the current dust control system, especially with the uptick in shipments.

“Since February, we have suspended the intake of dusty cargo,” said Pavel Oleynik, executive director of the Murmansk port.

“In February, there was already a 20% decrease in this kind of cargo compared to last year. We are also actively working with freight owners to technologically change the loading places so that these cargoes do not come to us at all,” Oleynik added.

It remains unclear which specific types of cargo Oleynik was referring to or if it can alleviate the problem in the future, given that coal has been the Murmansk seaport’s main business for years, accounting for over 80% of all freight.

Black lungs

Workers in coal terminals like the one in Murmansk are exposed to especially high concentrations of dust, said Anton Lementuev, a native of the Kemerovo (Kuzbass) region, Russia’s coal-mining heartland.

Yet even residents living far from these sites can face adverse health impacts due to the ease with which fine particles can travel, he added.

An open-pit coal mining engineer and an activist fighting coal industry pollution since 2014, Lementuev has seen Russia’s coal ports with his own eyes.

“In any port where open coal loading is taking place, a crane with a special bucket simply takes a portion of coal from an open pile, turns around and pours it into the hold,” Lementuev told The Moscow Times.

“This is all accompanied by dust emissions at every stage because the coal starts to break down into fine dust.”

А 2022 study by Murmansk researchers found that the amount of coal dust in snow samples taken in the city exceeded the maximum allowed concentrations under federal health and safety regulations.

Coal dust contains heavy metals that are hazardous to humans with prolonged exposure, studies show. In the worst-case scenario, coal industry workers can develop anthracosis, also known as “black lung disease.”

“Tiny dust particles build up in the lungs and are not expelled. Lung function gradually declines, leading to irreversible processes [inside the lungs] … and in the most severe cases, to premature death,” Lementuev said.

“Even if workers [in the Murmansk port] have proper respirators — let's say they are lucky and their employer invests in them — people outside the industrial area are also affected, and it's prolonged exposure.”

Although coal terminals use some pollution containment methods, such as anti-dust water cannons and windbreak nets that reduce the spread of dust by wind, these are only half-measures, Lementuev said.

He explained that enclosed coal handling in covered facilities at all stages is the only viable solution, even if it’s more expensive.

“If the authorities valued human life and health, they would push these companies to spend money on constructing enclosed warehouses with air purification, ensuring safety. So that workers don’t breathe this dust — they are as dirty as hell inside and out — and nearby residents don’t either,” Lementuev said.

“But since the value of human life [in Russia] is low, the profit of these loading companies takes priority.”

t.me/AoMurmansk

t.me/AoMurmansk

As the dust settling on the residents’ windowsills and turning the city's snow gray continues to fuel public grievances, the Murmansk trade port is busy expanding its operations.

One of Russia's primary coal hubs, the terminal increased cargo shipments on the Northern Sea Route (NSR) by 23% in 2023.

The port also loaded two huge Capesize vessels destined for Asia with coal last year, claiming they were the largest ships to ever navigate the NSR.

As Moscow aims to expand its exports to the east, the activity in the port of Murmansk offers a glimpse of the state of the Russian coal industry amid the third year of the war on Ukraine.

Navigating the storm

Over a year and a half since a coal embargo of the European Union — which had purchased one-third of all Russian coal sold abroad — the Russian coal industry has yet to see a significant downturn.

Official figures indicate that Russia’s total сoal production decreased by a marginal 1% in 2023 compared to the previous year, remaining at levels similar to pre-war volumes.

According to Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak, coal exports increased by 1% last year, rebounding from a 7.5% decline in 2022 compared to the previous year.

Despite the temporary setback in 2022 — when the industry was grappling with Western sanctions imposed during the first year of the war — experts say Russia’s coal exports have remained stable, with the country’s pivot toward Asian markets now fully underway.

Moscow had started looking eastward before the war, acknowledging in Russia’s 2020 coal strategy the need for change due to the EU’s shift away from coal in alignment with the Paris climate agreement. The sanctions have simply accelerated the process.

According to Novak, Russia sold nearly 52% more coal to China and 43% more to India in 2023 compared to the previous year, while the share of BRICS countries in Russia's total coal exports surged by about 46% in 2023.

Yet the transition will continue to take effort.

Russia has faced logistical hurdles, particularly in the Kuzbass, in its efforts to redirect its entire coal volume previously destined for Europe to the East.

“There's a significant problem with exports [in Kuzbass],” independent renewables expert Tatiana Lanshina told The Moscow Times.

“Kuzbass saw regular rail traffic jams last year because the current infrastructure simply cannot handle this much coal heading eastward,” Lanshina said.

Sanctions have also made it increasingly difficult for the Russian coal industry to strike deals with foreign partners, Lanshina said — and the agreements secured are less profitable than those previously established with the EU.

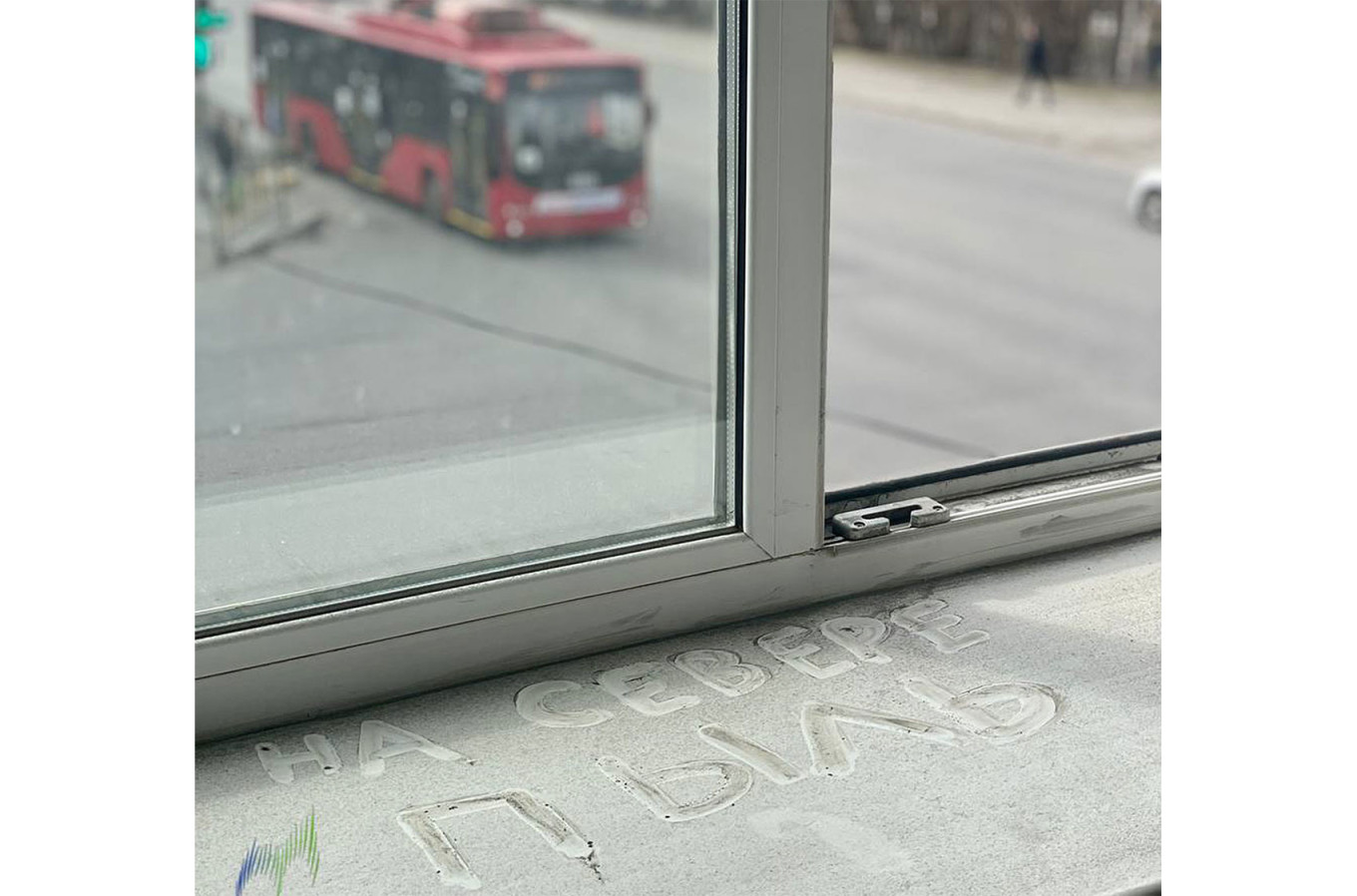

The message "There's dust in the north" written on a windowsill covered in coal dust in Murmansk.

t.me/groupmurmansk

The message "There's dust in the north" written on a windowsill covered in coal dust in Murmansk.

t.me/groupmurmansk

The industry also faces the looming possibility of a future crisis, with losses expected at the end of 2024 due to falling coal prices and rising logistics and loan servicing costs, the Kommersant business daily reported Tuesday.

However, Russia’s current bet on Asian markets, whose environmental and social policies are projected to lag behind those in the West, will ensure stable demand for Russian coal over the next five to 10 years, Lanshina said.

But in the longer term, the industry will “undoubtedly face significant challenges.”

“By the middle of the century, I believe the environmental agenda will extend to Asian countries as well, as all countries are interconnected, and global supply chains for goods are intertwined,” the expert said.

“For example, if Europe manufactures some product, it will naturally begin to demand that its Asian suppliers also address greenhouse emissions, workers rights and so on.”

Russian officials and senior managers at major firms are well aware that the global energy transition will reduce coal demand, Lanshina said, but they are unwilling to embrace the transition themselves.

Given the uncertain political and economic outlook for Russia, making long-term predictions may prove futile.

"Neither in the government nor in the companies does anyone think about the year 2050 or even 2030, because everyone is living day-to-day,” Lanshina said.

“It's important to sell now, extract as much as possible, export and earn money,” Lanshina said. “Nobody thinks about what will happen next.”

Despite the challenges posed by the West, the Russian coal industry appears to be staying afloat for now, leading some to question whether the sanctions on Russian coal have achieved their goals.

“Yes, Asian markets are not as profitable, and yes, Russia is not currently receiving the same level of revenue from its exports,” Lanshina said.

“There's less money overall, but still enough to continue the war.”

(1).png)

8 months ago

51

8 months ago

51