NEWS ANALYSIS

The election results have reshaped South Africa’s political landscape. How did it happen? And what happens next?

MK. That’s what happened. Like in the movie Jaws. Just when you thought it was safe to get back into the water, Jacob Zuma has returned to centre stage.

The uMkhonto weSizwe party’s sensational surge to almost 15% of the national vote put paid to any chance of the ANC retaining its majority.

Populism sells well in the modern age of politics, especially the ethno-nationalist sort. Europe has witnessed a return of it in recent years, and the same in the Global South. And that’s what drove change in this South African election, reflected in the performance of MK and the Patriotic Alliance (PA).

Established parties of the centre, such as the ANC, either went back or, like the Democratic Alliance (DA) and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), stood still. Other, smaller, centralist parties, whether new or old, struggled to attain a foothold — Rise Mzansi — or were extinguished — Cope.

But MK’s surge is not just the product of ethno-nationalism and its sibling, digital disinformation. Zuma’s popularity is enormous among large pockets of Zulu speakers.

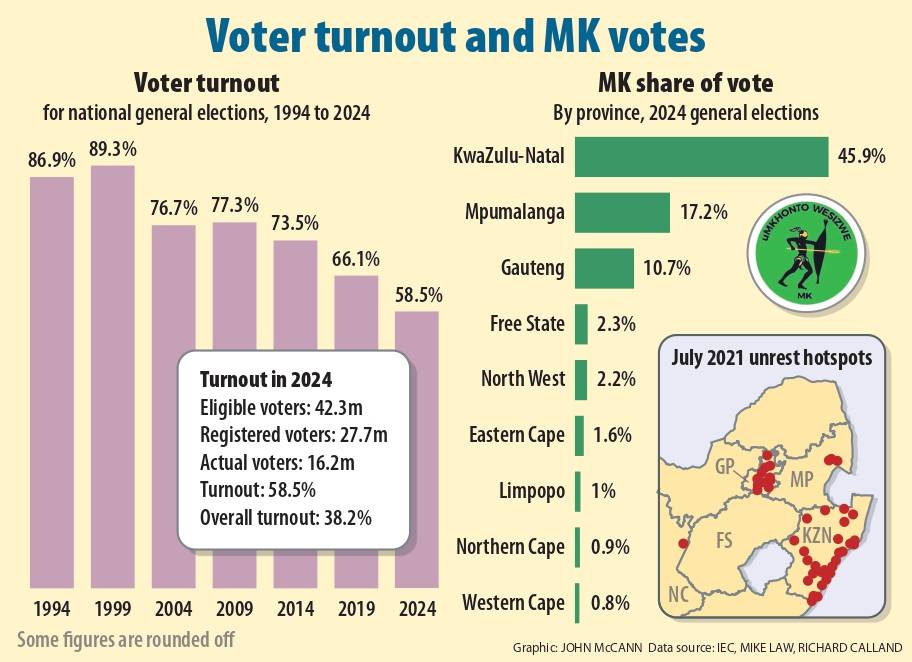

We knew that already. The country found out the hard way in the July 2021 unrest in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN). The “heat map” of the July 2021 unrest is eerily similar to that of MK’s electoral success.

The IFP manifesto launch in Durban on 10 March. (Rajesh Jantilal/AFP)

The IFP manifesto launch in Durban on 10 March. (Rajesh Jantilal/AFP)This is not to crassly suggest that all Zulu communities are violent. But it is to point out that there is a risk — that those places where people who heeded the call from Zuma and his family to rise up in 2021, after his incarceration for contempt of court, are also the places where MK got the most support in the election.

And populists tend to get their voters to turn out in higher numbers. They get their supporters agitated. More moderate political actors might be more right, but they are also more boring, which isn’t good for turnout.

So, another factor here was that turnout was higher in KZN than in any other province — about 4% more than the national average.

Outside KZN, MK’s next-best percentages came in from Mpumalanga, which has a bigger proportion of Zulu speakers than any province outside of KZN. Then, it also hit double digits in Gauteng, which has the highest gross number of Zulu speakers outside of KZN.

It barely hit 2% in any other province. So, it’s an ethnic party — the evidence is overwhelming.

That doesn’t mean the entire Zulu nation voted for Mr Zuma and his break-out party. A shout-out must go to the IFP, which somehow managed to grow is KZN vote, and increase its seats in the National Assembly, in spite of such a sensational political onslaught on their KZN stronghold.

Like all major political movements in South Africa, the IFP has had some volatility in its complex history. But, in the modern age, it has evolved into a very respectable actor.

There are some good and capable people in the IFP’s top leadership, including its dignified leader Velenkosini Hlabisa and the seasoned parliamentarian Narend Singh, and so it would probably be a very reliable partner in a coalition government.

It is important to have some KZN representation in the top rungs of South Africa politics. It might even be critical for keeping the peace.

At the ANC’s 2022 national conference, there were no prizes for the KZN ANC. Its own fault, of course, having put itself in opposition to party and national president Cyril Ramaphosa’s faction, which was about to sweep the floor.

But, in any country, if the largest ethnic group doesn’t have a decent stake in the body politic, it will forge its own.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)That’s what MK did, using those same ANC KZN structures. It was a sabotage job, from the inside. A classic Zuma-style intelligence operation, sleeper cells and all.

MK organised in KZN wearing ANC regalia, mobilising ANC branches though ANC leaders, according to numerous sources inside the organisation (the real one).

Another party that didn’t survive the KZN hit is the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). It has declined. Many of its lost votes were in KZN, where it seems the party had been borrowing some of Zuma’s voters who couldn’t support Ramaphosa’s ANC.

But even outside KZN, the EFF’s growth came to a halt. That’s two elections in a row now, after a similar oscillation in 2021. Political capital generally rises, then it falls. Malema must be asking, “Where to from here?” for his Red Berets.

Already, he’s singing off a different hymn sheet — reflecting his reduced power — with fewer than one in 10 voters supporting his militant, but one-trick-pony, political positioning.

He’s clearly re-positioning fast and adjusting his ambition to be a king-maker in the new coalition world.

EFF leader Julius Malema votes on 29 May. (Paul Botes/AFP)

EFF leader Julius Malema votes on 29 May. (Paul Botes/AFP)He wants in on the new government, that’s for sure. There’s no other endgame for him, at this point.

The DA did well — even if its critics are spinning it otherwise. It kept a comfortable majority in the Western Cape and increased its seats in the National Assembly. It has become the largest party in the metros.

Job well done, from its perspective.

The DA’s expansion, however minor, is even more impressive in the context of the PA’s growth among working-class coloured voters, a critical constituency to have in order to hold a majority in the Western Cape, and the Northern Cape.

The DA took some losses from the PA, as did other parties, but won them back elsewhere. It clawed back votes from the Freedom Front Plus and even made inroads into ANC votes in some parts of the country.

It was not a good election for the “chattering-class” parties, such as Rise Mzansi, Build One South Africa and Good.

Or for ActionSA. Being the new kid on the block only sells for one election. It’s a tough and unforgiving electoral marketplace. After that, you need to stand for something clear and occupy an ideological space if you’re going to keep growing.

On the positive side of the balance sheet for Election 2024 there is, first of all, the grace and dignity with which the ANC accepted its hard fall to well below 50%. This should not be underestimated, given how many election losers seek to cling to power or claim rigged processes.

Second, despite some disappointing technological and other glitches on election day, the IEC withstood the pressure and deserves particular praise for staring Zuma down last weekend, when he sought to intimidate it into postponing the declaration of the election result.

Third, it could herald the start of a new era, with a competitive multi-party democracy.

Or, on the other side of the balance sheet, the start of a period of fractured politics, where populist parties — now with at least 26% of the vote combined (EFF, MK and PA) — fill the vacuum created in the centre-ground, as ANC dominion dissolves.

Turnout fell below 60% for the first time in a national election, on the back of one-third of eligible voters turning their backs on democracy and not registering.

Bottom line: only one in seven eligible voters voted for the ANC. The transition from the era of the dominant party is well and truly over and the ANC is struggling for legitimacy.

So, that’s the report card. But what does it mean?

It means a hung National Assembly, more open to different scenarios than was initially predicted. And hung provincial legislatures in KZN, Gauteng and Northern Cape (where the ANC is just a seat short of a majority).

Let’s focus on the National Assembly, because the deal that is struck there could shape the deals to be done in the provinces.

This is a critical moment in South Africa’s fate. The centre could hold or things could fall apart. And it doesn’t have much time to decide.

ANC supporters at a polling station in Hout Bay, Cape Town, on 29 May. (Dwayne Senior/Getty Images)

ANC supporters at a polling station in Hout Bay, Cape Town, on 29 May. (Dwayne Senior/Getty Images)The first sitting of parliament must be held within 14 days of the declaration of the result (which was on 2 June), at which a president and speaker must be elected.

Constitutionally, it is plausible to elect these office bearers without an outright majority (that is, 201 MPs). But it would be dangerous to do this, especially from Ramaphosa’s perspective, as a president elected without the majority support of parliament is vulnerable to a motion of no confidence from day one.

If a president is removed in a no-confidence vote, it counts as the end of a presidential term, and presidents in South Africa are limited to two. Ramaphosa has already served one. If he’s removed in this manner, he can’t be president of South Africa again.

So, especially from the ANC’s perspective, that makes it particularly important to have at least a skeleton agreement in place in the next two weeks that can account for a majority of MPs in the National Assembly.

It might not be a fully fledged coalition agreement, in the strict technical sense of the term. It could be something less, such as a supply-and-confidence arrangement to prop up a minority government. But that, too, would have a price, such as key positions in the legislature and elsewhere in the state architecture.

Coalition negotiations are notoriously difficult to predict and anything could emerge. Talks have been held with pretty much all parties, as well as the ANC’s alliance partners.

The bids are in and it will ultimately be left to the ANC national executive committee to choose its bride.

Many in the business community and elsewhere would like to see a deal between the ANC and DA. That could happen. The DA is open to it, even if it might be a tough sell to some of its voters (the same, of course, for the ANC).

DA leader John Steenhuisen delivers a speech in Benoni on 26 May. (Phill Magakoe/AFP)

DA leader John Steenhuisen delivers a speech in Benoni on 26 May. (Phill Magakoe/AFP)There is a good cohort in the ANC who would like it to happen too. The DA has the attraction of being a more reliable coalition partner than the rest, showing some appreciation for good coalition practice in its wobbly introduction to the local government sphere.

And a stable and predictable coalition partner is in the ANC’s best interests, as it is likely to inspire economic confidence at a time when it is in short supply.

A three-way agreement between the ANC, DA and IFP would probably be even better. It would square the game in the KZN provincial legislature. It could make the deal an easier sell to the DA-sceptics in the ANC, positioning it as something broader than just a straight ANC-DA alliance.

It would include strong representation for KZN, key to national peace — the old guard, so to speak, holding the centre, against the rowdy new kids on the block.

It would be a stable and accountable basis for preserving and advancing a progressive political project.

But DA cynicism is a real thing in the ANC and its alliance partner trade union federation Cosatu.

Some of it breeds from imagery of the past, some is at least ostensibly ideological, although the parties really aren’t as far apart as their campaign rhetoric suggests — especially now that the radical economic transformation bloc has, to a very large extent, already left the ANC and set up shop elsewhere.

Party leader Gayton McKenzie at the Patriotic Alliance rally on 10 May in Athlone, Cape Town. (Brenton Geach/Gallo Images)

Party leader Gayton McKenzie at the Patriotic Alliance rally on 10 May in Athlone, Cape Town. (Brenton Geach/Gallo Images)

The allergic reaction of Cosatu and other “old left” factions of the ANC is understandable. But it is not strategic.

Asking what coalition arrangement would best advance working-class interests is an important and legitimate question. But, a return to the plunder of state capture under Zuma, with the concomitant breakdown of institutional capability and integrity in the state, or the parasitic compradorship of the EFF is not the answer.

These are faux revolutionaries. They are not left parties in any real sense of the notion. If anything, they are counter-revolutionaries.

Progressive politics is best served by maintaining the rule of law and constitutional rights and freedoms; by continuing to rebuild state institutions and capability. The most stable and accountable coalition government will be able to deliver a transformative agenda.

But the ANC national working committee in its “wisdom” has decided to explore the possibility of an ultra-broad equivalent of the “government of national unity” concept and include a much longer list of parties in the new government.

It must be a non-starter. For one, the DA surely won’t do it. Sharing power with the ANC already presents significant electoral risk for the DA and supporting a government that involves the EFF is asking too much.

So, if that proposal is seriously pursued, it will push the game towards Malema and the ANC + EFF + dodgy smaller parties — a deal that used to be called the doomsday scenario — until Zuma reminded us that there might be something even worse.

uMkhonto weSizwe’s Jacob Zuma at the IEC results centre in Midrand on 1 June. (Waldo Swiegers/Getty Image)

(1).png)

7 months ago

52

7 months ago

52