After being held up by half a year of partisan infighting in Congress, U.S. President Joe Biden signed a $61 billion package of desperately needed aid for Ukraine, showing that Kyiv’s most vital ally will continue to support its fight against Russia’s invasion — at least for now.

But while Kyiv has welcomed the news, the six-month delay has allowed Russia to exploit Ukraine’s weakened air defense system to deadly effect.

Even if promised aid from the U.S. and Europe moves quickly, it will likely not reach the front lines for weeks, giving Russia a window of opportunity it could take advantage of.

With the front lines barely budging over the past year, the war in the skies has started to take a greater toll, with Russia pummeling cities and infrastructure deep into Ukraine. In April, Russia destroyed the largest power plant in the Kyiv region. According to the most pessimistic estimates, Ukraine’s thermal power plants have lost 85% of their generating potential due to Russian strikes in March and April.

While Russia did not significantly scale up the number of weapons used in these attacks since December 2023, they were more impactful because Ukrainian forces were unable to intercept them.

Analysis from the U.S. think-tank Institute for the Study of War found that Ukraine was increasingly failing to intercept even half of Russian missiles since March 22.

Russian strikes now include a combined package of cruise missiles, drones and ballistic missiles to overwhelm Ukraine’s overstretched air defenses.

While Shahed drones can be shot down by teams of mobile fire units shooting machine guns and shoulder-launched artillery from the back of pickup trucks, missiles — the fastest of which fly at 10 times the speed of sound — can only be countered with more sophisticated weaponry.

Moscow has also started to employ cruise missiles equipped with technology that fires decoy flares to misdirect Ukrainian missiles that track the heat signature of their target to hit them.

Another significant tactical development by Russia is its increased use of glide bombs, which has soared sixteenfold from 2023. These are converted from the plentiful Soviet-era bombs already in Russia’s inventory, which once upgraded with wings and guidance systems can fly 65 kilometers after being dropped from planes behind the front line.

They proved their effectiveness when Russia captured Avdiivka in the Donetsk region in February. Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Dmytro said Russia dropped 700 glide bombs in the six days from March 18, days after a Russian Iskander missile destroyed two Patriot batteries.

A firefighter at the Trypilska power plant near Kyiv, which was destroyed by multiple Russian missiles on April 11.

State Emergency Service of Ukraine

A firefighter at the Trypilska power plant near Kyiv, which was destroyed by multiple Russian missiles on April 11.

State Emergency Service of Ukraine

These tactics have forced Kyiv to make difficult decisions about where to deploy its limited resources.

“We’ve seen that as shortages have worsened, Ukraine has had to allocate a lot of its air defense assets to protect large population centers in the rear,” Riley Bailey, an analyst from the Institute for the Study of War, told The Moscow Times.

“That means a lot of the frontline is underserved or doesn’t have air defense at all. That lets Russian tactical aviation conduct glide bomb strikes that aren’t accurate, but en masse cause widespread destruction to Ukrainian lines.”

In Russia’s first response to the bill’s passage through the House of Representatives, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu vowed to step up attacks on logistics centers and storage facilities for Western weapons in Ukraine. Riley told The Moscow Times the time it takes for Ukraine's air defenses to be replenished could provide Russia with a window to intensify its attacks.

It is still unclear whether the U.S. will deliver another Patriot air defense battery to Ukraine, having only sent one so far. Germany, which has already delivered two of its 12 Patriots to Ukraine, has pledged to send another unit, and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte offered to buy Patriots from countries who were hesitant to part with them.

These systems are particularly crucial for Ukraine because they can fire ammunition capable of intercepting Russia’s hypersonic missiles, which have been slipping through Ukraine’s air defense net at particularly high rates.

Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Dmytro Kubela said that ongoing negotiations for four further units are complicated by countries wanting “compensation” for their donation.

“I think the U.S. army probably has one spare,” he said.

But these systems will be insufficient to build a defensive umbrella over all of Ukraine, the largest country fully within Europe. Analysts say Ukraine will be more able to protect its cities and soldiers if it can strike targets in Russia and the occupied territories.

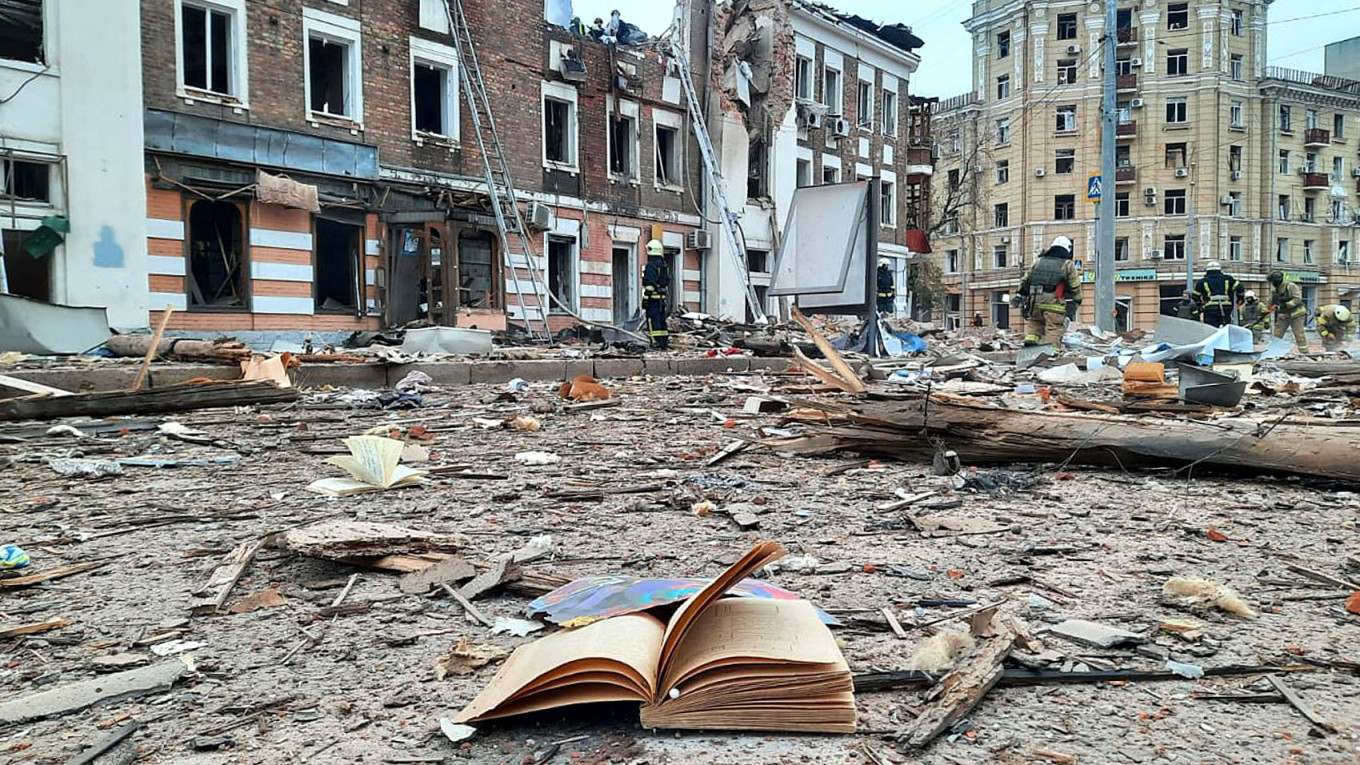

Destruction in Chernihiv after Russian missile attack on 17 April 2024, which killed 18 and injured more than 60 people.

State Emergency Service of Ukraine

Destruction in Chernihiv after Russian missile attack on 17 April 2024, which killed 18 and injured more than 60 people.

State Emergency Service of Ukraine

Washington has long expressed reluctance to send Ukraine weaponry capable of striking targets in Russian territory for fear of escalating the war.

But the week before the bill’s passage, the U.S. secretly shipped long-range ATACMS with a range of up to 300 kilometers to Ukraine, who used them to strike troops in the occupied Ukrainian city of Berdiansk on the shores of the Sea of Azov.

Ukraine previously used long-range weaponry, such as Storm Shadow missiles donated by Britain, to push Russia’s Black Sea Fleet out of Ukrainian waters and destroy submarines that launched missiles toward the country. British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said Tuesday that his country would provide more of these weapons to Ukraine.

This fear of escalating the war meant it took Washington until August 2023 to allow Kyiv’s allies to donate F-16 fighter jets to provide cover for Ukrainian ground forces and bolster the country’s air defense.

Currently, Ukrainian pilots and ground crew are being taught in Romania how to fly and maintain the aircraft. Officials say about 12 pilots could be ready to fly F-16s in combat by July. But only six of the promised 45 jets may have been delivered by that point, less than a full squadron.

While Zelensky welcomed Denmark and the Netherlands' commitment to be the first countries to donate F-16s to Ukraine as a “breakthrough agreement,” other voices have been more cautious. U.S. officials privately said F-16s would not be a game changer due to Russia’s own air defenses and electronic warfare that could interfere with the jets’ radar.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky (L) and Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen sit in a F-16 fighter jet on August 20, 2023.

Photo by Sergei GAPON / AFP

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky (L) and Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen sit in a F-16 fighter jet on August 20, 2023.

Photo by Sergei GAPON / AFP

“If Ukraine’s F-16s can survive Russia’s air defenses and has good reconnaissance, it could force Russia’s planes that drop glide bombs towards Kharkiv and Ukrainian soldiers further back from the front line, where the effective range of those weapons will be reduced,” Retired Air Marshal Edward Stringer, who served as director general of Britain’s Joint Force Development, Strategic Command, told The Moscow Times.

Stringer also said that although donating F-16s was the right decision, they may be less effective over Ukraine than in other NATO missions, where they are deployed as part of a package with other NATO jets to support them.

Even if these obstacles can be overcome, Ukraine would still be reliant on the U.S. and Europe to produce and supply expensive air-to-air missiles.

Destruction in Kharkiv after Russian missile strike.

State Emergency Service of Ukraine

Destruction in Kharkiv after Russian missile strike.

State Emergency Service of Ukraine

Kharkiv lies just 30 kilometers from Ukraine’s border with Russia, leaving it particularly exposed to missile and drone attacks. Sirens have become an inescapable part of life for the city’s 1.3 million residents — roughly half of its pre-war population — who have opened schools and even a ballet theater underground.

Residents only have electricity for a few hours each day after Russia destroyed the three power stations that supply the city. Russia has started to time its attacks to coincide with these power outages, forcing residents to wait in agony for cellphone signal to resume so they can reach their loved ones.

Ukrainian officials have voiced concerns that Russia is intensifying its bombardment of Kharkiv, as well as spreading propaganda, to make the city unlivable. Russian officials have signaled their intention to create a buffer zone along Ukraine's northern border.

Ada Wordsworth, head of the KHARPP NGO which supports Kharkiv region villages, told The Moscow Times that people felt a huge sense of relief at the news that more U.S. support was on the way.

“However, this relief comes with a fair amount of resentment because of how long it has taken, and how many lives — civilian and military — have been lost,” she said.

“There's also a limited hope for the impact this funding will have in terms of protecting the sky over cities like Kharkiv, which are so close to the Russian border, unless Ukraine is allowed to use these weapons to strike Russian territory,” something Washington has said it does not support.

Whether Kyiv’s allies can continue supplying weapons to Ukraine heavily depends on their ability to manufacture expensive equipment.

Despite international sanctions, Russia has managed to secure millions of munitions from North Korea and Iran, as well as shoring up its domestic production and refitting older equipment. Though Ukraine fired more artillery than Russia in the summer of 2023, delays in aid and Russia’s relatively strong production have allowed Moscow’s forces to fire six shells per every one Ukraine can muster.

“I think Europe missed the geostrategic moment two years ago,” Stringer told The Moscow Times. “Had our leaders had the appropriate depth and seriousness of thought, they would have looked at our defense industrial base and ramped up our own production. I think the fact they recognized there was a problem but did not do anything to solve it makes it worse.”

(1).png)

8 months ago

15

8 months ago

15