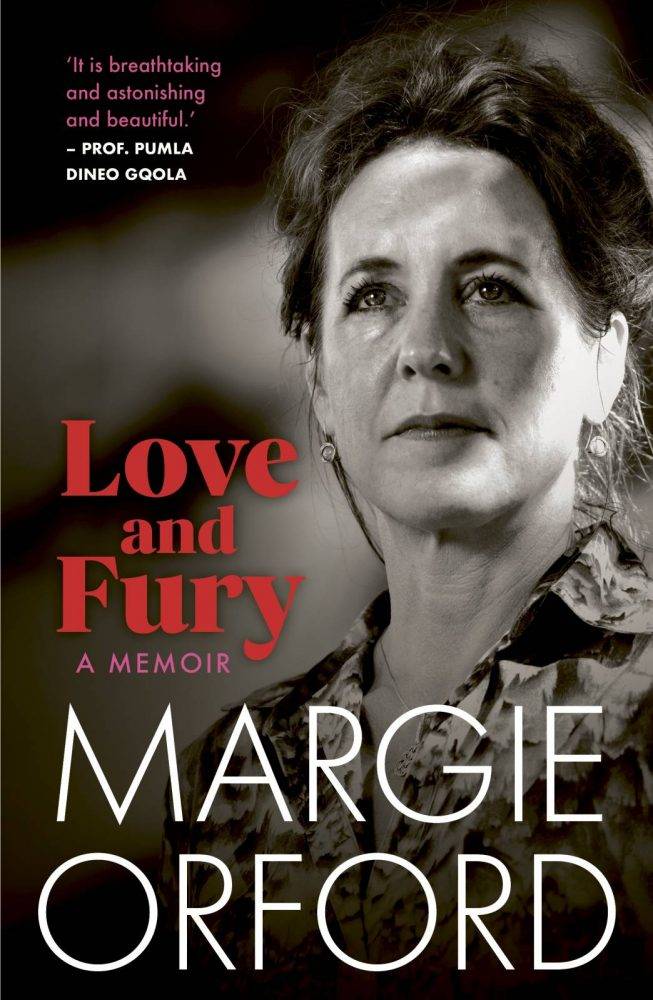

Word power: Margie Orford’s recently released memoir Love and Fury is gripping, but not an easy read, telling of marriage, divorce, depression and sexual assault. Photo: Bella Galliono-Hale

If it hadn’t been for writer’s block, the book lying between the writer and me on the coffee shop table may not have been there. In fact, the writer herself would probably not have been here on this late autumn Friday morning in Johannesburg.

Unlike us two hacks, the writer’s therapist did not find her joke about why she couldn’t commit suicide funny at all.

Internationally acclaimed and respected author and journalist Margie Orford tells the story in her powerful, recently published memoir Love and Fury of a freezing London day in January 2018, when she felt her career as a writer had shuddered to an end — the one thing she knew, writing, had abandoned her. It made her desperate. It made her mad.

“I did not want to work,” she writes. “I did not want to use my talent. I did not want to be alive. How, though, does one go about eliminating oneself without causing a disturbance?”

She had tried for months to write a suicide note but couldn’t.

“I can write anything,” she tells me over espresso and a croissant. “Copy, reports, thrillers, romances, anything … I can write it.”

Orford looked online at “literary” suicide notes. “There are many,” she says. “[Russian writer Vladimir] Mayakovsky’s suicide notes … it’s so florid and embarrassing.”

She looked at how Virginia Woolf’s addressed her note to her husband: “Dearest, I feel certain that I am going mad again …”

But Orford did not hear voices like Woolf did. “I heard muffled silence; felt my lack of ballast,” she writes in Love and Fury.

She told her psychoanalyst in Hampstead, where she lived then, about her unsuccessful attempts.

“Writer’s block. So far, it’s kept me alive.” He didn’t laugh at her gallows humour.

She writes: “He looked at me over slender steepled fingers and said, ‘It’s what’s alive in you — your writing, your creativity — that won’t let you finish.’”

Orford picks up on it in our conversation.

“He didn’t let me joke about it,” she says in measured tones. “He made me look at what was the impulse which I wouldn’t look at … this feeling that I wouldn’t address.

“And then the very thing … that I couldn’t do, which was write another novel…

“You know, the capacity to write, which is to create, which is to make sense.”

She pauses.

“I’m here. Like this.”

We both smile.

“I’m glad for writer’s block,” I say. “Because what would I have done today?”

“Yeah, exactly.”

Orford, who is still based in London, is in South Africa to promote her captivating, at times dark, autobiography.

She will make a turn in Namibia, but her main destination is the Franschhoek Literary Festival. “I’ve done it many times. Oh, it’s nice!”

She is an easy conversationalist, with a fine sense of humour, but not unwilling to delve into uncomfortable places, so I can understand why she has cracked repeated invites to the festival.

And with Love and Fury she tells the gripping story — political and personal — of her life so far, surviving marriage, divorce, depression, sexual assault and loss.

Orford was born in London to South African parents but has lived through eventful periods in Namibia and South Africa during the two countries’ tumultuous times of transition, working as an activist, journalist, film director, publisher and teacher. Yet, she says she never set out to write a memoir.

However, the “queen of South African crime-thriller writers” had stopped writing her massively popular Clare Hart series. And then the novel Orford had written didn’t sell.

It was around 2017, and her agent said: “Write a memoir.”

“Memoir was, like, a big thing. I thought, ‘Oh, alright,’” she says, “and I’d done a couple of pieces for Granta [the British literary magazine].”

The other reason for Love and Fury was literally to survive.

“In retrospect … I think the reason I wrote it was to try and keep myself going. And keep myself alive and sort of … make sense of things again.

“But it was only after the fact that I realised that’s what had happened.”

The previously rejected novel — The Eye of the Beholder — has since sold and was published in 2022 (its sequel is due next year).

“And I think, in that book, I started taking on in the writing really how violence shapes people. And then I was also thinking how it’s shaped me in a number of ways.

“And it was a reckoning … first in fiction. And then in the memoir.”

As journalists and writers in deeply violent societies we learn to cope by flicking our emotional switch. “We were trained in a way that you switch off your feelings. That you switch off the trauma.

“The response — it was a kind of macho way,” Orford says as she orders her thoughts, picking at the flakes of her croissant.

“You know, macho female, and I suppose it was like Freud’s return of the repressed … it makes sense of us.”

As a lifelong feminist Orford writes that, “I could not bear the thought of being dependent, of being a leech on my husband, of needing someone else to pay my and my baby’s way. That filled me with horror and shame.”

I ask her what the most important lessons are a male reader can get from Love and Fury about being a woman in the world today.

“Probably they shouldn’t marry me… that would be my first advice,” she says with a wry chuckle. “Just as an aside … a lot of men have been reading the book. I’ve been really struck by it because men I know and men I don’t know, just write to me.”

Orford is a survivor of sexual assault. One of her friends said he was consumed by the book and added: “I believe you.”

Whenever she told other women, they believed what had happened to her but, “It was striking to me how important it was that this man believed me … then it enabled me to believe myself.

“That sounds like a profoundly anti-feminist sentiment but one of the crucial things for me in terms of understanding and writing about all this stuff … and getting better and worse was understanding just how I didn’t believe myself.

“And women don’t believe themselves very often … but, when a woman tells you something, you need to believe her.

“Watch how women walk in the street — you feel afraid … you always calculate it and it’s a thing that men don’t live with all the time.”

She recounts sitting around a table with friends at Oxford where she was teaching. They were all in their 50s and all of them had experiences of rape in their late teens and early 20s in similar ways.

“And I thought, ‘Okay, all of us carry these things.’ So, for men, pay attention to what women feel … and do something about it.”

Love and Fury is a compelling book, but by no means an easy read, especially where Orford writes about the violence meted out to women’s bodies.

In 2001, equipped with a PhD from the City University of New York, she moved back to Cape Town where she had studied years before.

This is how Orford sets the scene about returning to what she started her working life as — a journalist: “‘When I get back,’ I wrote in my notebook, ‘I will arm myself with one question: why?’ And yet, as I wrote those words, a familiar sense of doubt — a close cousin of futility — stopped my writing hand and I put down my pen.

“Words cannot repair torn skins. Even though they must be spoken, they do not right wrongs.”

In Cape Town, she writes, “there were many times when the dead and wounded women I was writing about inhabited my body.

“I heard their outraged voices in my head asking, ‘Why me?’ and their despairing imperative: ‘Do something!’ All I could do to quieten them was to write.”

Orford eventually turned to fiction. “Writing fiction about crime was the only way I could think of to capture South Africa’s spectacular post-apartheid violence and its effects on ordinary people.”

I ask her about the switch back to non-fiction to write her memoir.

“I found it really difficult,” she says. “Was it worthwhile? I don’t know. In many ways it is for me like writing fiction — in the way that you construct a world for the reader.”

Orford knows this world is important.

“I went through some difficult things and I’ve come to understand … maybe this [book] will be helpful because I’ve been helped by so many of the books that I’ve read in my life.

“So, I did get to really appreciate the generosity of the books that I’ve loved because they helped me navigate the world.”

She says as you get older you “care less what other people think of you but care more about the world and people”.

However, there are three people whose opinions about Love and Fury still mattered a lot: her daughters, Olivia, Hannah and Emma.

“They’re proud of their mum; they think I’m very brave,” Orford says with an almost relieved smile.

(1).png)

7 months ago

56

7 months ago

56