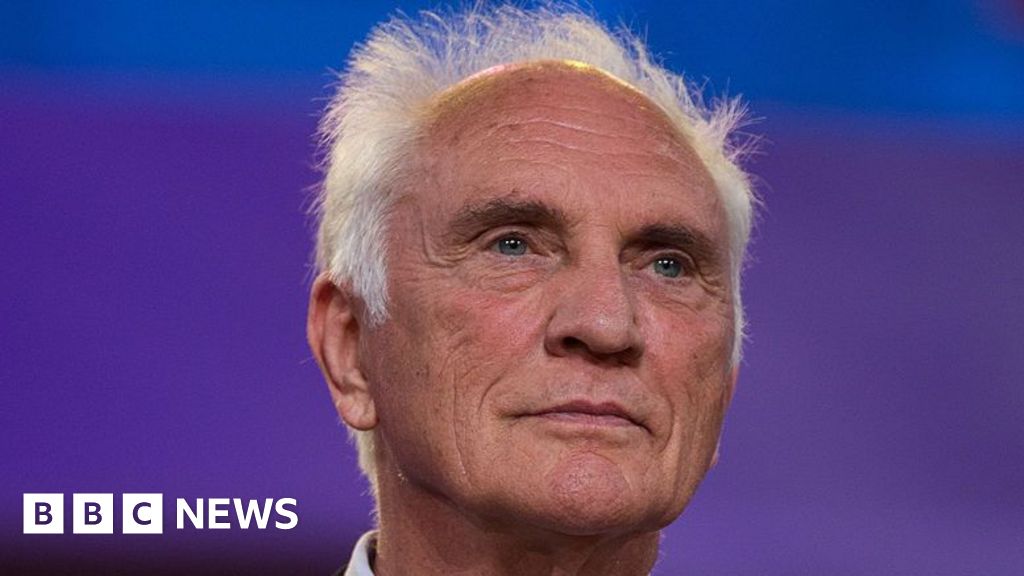

- HIV researcher Francois Venter heads up Ezintsha, the Wits-based medical research centre, and is known for speaking without any regard for self-preservation – something a lecturer friend calls “borderline cancel language”.

- Venter grew up under apartheid, weaned on Springbok radio and weekly military-style marching drills in Phalaborwa, Limpopo, where he was one of seven children and – until he landed at Wits – had “never met a black person who wasn’t a servant”.

- Sean Christie talked to him about his unorthodox inaugural full professorship lecture, his work during the height of the Aids crisis, the Trump administration’s defunding of HIV and scientific research and his shoot-from-the-hip fix of our healthcare system.

An inaugural lecture is a formal event thrown by a university to commemorate the lecturer’s appointment to full professorship. They are usually pinnacle-of-career moments.

Francois Venter’s inaugural lecture at the University of the Witwatersrand in 2023 was not typical.

He began by recounting years of successfully dodging requests to deliver the lecture, often blaming the university’s email system for his lack of response. While he dutifully name-checked his professional role models and heroes, he also took the opportunity to give credit to his tennis and rock climbing coaches. Interwoven with these acknowledgements were lively anecdotes - such as drinking tequila with Dexter Holland of The Offspring rock band (who earned a PhD in molecular biology in 2017) and receiving not one, but two, untimely calls from Standard Bank (“I swear I turned this off …”).

Venter’s aversion to formalism, it seems, remains resolutely untreated.

“I hate, hate, hate talking about myself,” he warns.

We are sitting in the immaculate boardroom of Ezintsha, the Wits-based medical research centre that Venter leads.

Venter’s rock-climbing adventures have taken him from Table Mountain to Vietnam, Las Vegas, Nevada, in the US, and onto this mountain near Vancouver, Canada.

Ezintsha came to international attention in 2019 after the results of a clinical trial called ADVANCE were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The study showed the effectiveness of new HIV therapies and, perhaps more importantly, demonstrated why it is important that clinical trials be conducted in the contexts in which the drugs are mainly consumed.

The therapies worked, but as Venter puts it, “with complications peculiar to local populations, far from the sanitised world of curated pharmaceutical studies done on healthy white men.”

Venter, by this time, was already well known for his work in HIV, not only for his scientific outputs but for taking up cudgels on behalf of people living with HIV. Venter’s response to being singled out is predictable: “There are so many people in the HIV world who did much more, and more bravely.”

It is the refrain of many treatment activists, and it was no deterrent to my questions about his childhood in the Lowveld town of Phalaborwa.

Venter, second row, third from left, with classmates at Hoërskool Frans du Toit.

“The town has a paint colour named after it – Phalaborwa Dust – a sort of dull grey, which says everything, really,” says Venter, who was born in 1969, the first of seven children.

Venter’s Afrikaans-speaking father worked as an accountant for the Palabora Mining Company, while his English mother ran a creche.

“You couldn’t have a family that size today,” he says.

“They managed because the company subsidised everything from education to golf club memberships.”

In a time of grand apartheid, Venter’s world was particularly white and insular.

“Growing up, I never met a black person who wasn’t a servant,” he admits.

Venter, in the back row, was born in 1969. The first of seven children, his father was an accountant for the Palabora Mining Company and his mother ran a local creche.

“I worked like crazy at school, knowing that was my ticket out of there,” says Venter, who worried his lowveld credentials would make him the odd man out at Wits medical school.

“Instead, I walked into this amazing diversity of people. For a boy who grew up on Springbok radio, it was more than I had dreamed of,” he says.

Cancel language

Venter is tall, powerfully built. The sharp edges of a forearm tattoo peek out of the sleeve of a black puffer jacket. His disposition is nervous, though, his speech often self-effacing, although mention one of his many bugbears and a quiet fury brims. Venter is known for speaking without any regard to “self-preservation”. Like a good journalist, he calls it as he sees it.

Venter named one of his cats Fauci, on the right, after former US health czar Anthony Fauci, who helped steer the Covid-19 pandemic in the US.

The comparison pleases Venter, who was editor of the campus newspaper, Wits Student, in 1991. The publication had been overtly political since depicting Prime Minister John Vorster in a butcher’s outfit in 1973.

“I enjoyed the cut and thrust of the media, and understanding its place in political life,” says Venter, who credits journalism with making him a better HIV researcher and political organiser.

He describes his involvement in student politics as an almost involuntary act, akin to staying afloat in a turbulent river.

“The late 80s were some of the worst for apartheid repression. Fellow students were being detained and tortured, their families maimed and disappeared. There was nowhere for a white person to hide, and joining the fight [against apartheid] was the only moral choice.”

Venter, left, playing pool in res at Wits University with Damian Clarke, now a well-known trauma surgeon at UKZN.

Medicine, in those first years, was at the edge of Venter’s concerns. He maintains he was a “mediocre student” although he pulled his socks up in his fifth year.

Dying in Baragwanath

Healthcare provided Venter with a clear view of the twistedness of apartheid policy.

“You go into the black hospitals and it’s like, jeez, the things that are happening there. Meanwhile, white people are receiving world-class care,” says Venter, who did his “house job” (residency) at Hillbrow Hospital, which is where he first encountered HIV as a student.

“It was the beginning of that incredible surge in numbers that occurred between 1993 and 1997.

The first cases I saw were returning political exiles,” says Venter, who experienced an internal snap after an incident in a Yeoville restaurant.

“It was 1995. Rocky Street was still quite eclectic and happening, and I was hanging out in a restaurant run by this Caribbean guy I knew. He had booted out a young drug addict, who went across the street and bought a knife, came back and stabbed him in the heart. It was 10am. I tried to resuscitate him, but I had nothing. He bled to death in front of me, and I was like, f*ck South Africa and its trauma and violence.”

READ | Motsoaledi’s big HIV treatment jump: Is it true?

Venter boarded a plane for the United Kingdom, and a hospital job he found “terminally boring”.

By 1997, he was back in Johannesburg, specialising in internal medicine. The HIV epidemic was at its zenith, and hospitals across the country were overwhelmed.

“In some of the hospitals, like Bara (Baragwanath Hospital), you just left patients in casualty, and they would die there and go out the door.

“In Joburg Gen (Johannesburg General Hospital, today Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital), you put them on the floor in the corridors, and they died there waiting for a bed. It was brutal,” says Venter.

“The numbers had surged with a suddenness and severity that we still don’t really understand. Nelson Mandela was trying to prevent a race war. There really wasn’t much that he, or anybody else, could have done. I didn’t understand the transmission enough, and we didn’t have the tools to prevent it.”

Toxic - and incredibly effective

On completion of his specialist time ,Venter was burnt out and unsure of what to do with his life. He was interested in HIV, sparked by his experience of looking after a haemophiliac in 1997.

“The patient was one of a group that had HIV after receiving infected blood imported from the US by the state in the 1980s.

“The apartheid government took a decision to pay for their treatment with what was then extremely expensive antiretroviral therapy (ART), and the ANC government continued this,” says Venter, who was amazed at the impact of the drugs on his patient.

“I saw this patient in ICU just come off a ventilator, which just did not happen in those days.”

Francois Venter, third row from top, centre, at a 2014 HIV conference in Geneva, Switzerland with some of the top international HIV/Aids experts.

Venter was offered a job with the Wits-based Clinical HIV Research Unit by world-renowned HIV expert Ian Sanne, who, says Venter, “taught me how to do clinical trials, how to play with these toxic, incredibly effective drugs, and it was really the first time I was able to start seeing myself as someone who was going to get involved in HIV. The drugs have evolved since then, now more effective with almost no side effects.”

It was also where Venter started interacting with the NGOs and activists then taking the fight for affordable antiretroviral therapies to the government.

The Treatment Action Campaign had started smuggling them into the country. “It was devastating, though, watching them fighting our government to even acknowledge HIV existed, while their members died needing those drugs. The hypocrisy of senior political figures, many of whom had family members on ARVs (antiretrovirals) I was treating, yet didn’t call out Mbeki, is unforgivable.”

He then joined Professor Helen Rees’ Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Initiative and began working out of Esselen Street Clinic, an old Hillbrow facility home to the first South African HIV testing site, and from where he ran a huge US government-funded HIV support programme for the next decade across several provinces, gaining experience in expanding primary care approaches in chronic diseases.

Sponsored by

Since those heady Esselen days, many important clinical trials, HIV programmes, research papers and court cases have gone under the bridge, and Venter has become part of the moral conscience of South Africa.

For years, Ezintsha was based in a Yeoville house and Hillbrow back rooms, around which sewage spills split and foamed. Now, it occupies two floors of a large office block in Parktown, an environment of biometric access controls and curvilinear glass, employing 150 people. On the upper floor is the Sleep Clinic, where patients with suspected sleep disorders lie back on R50 000 mattresses sponsored by the company.

READ | Struggling with a sleep disorder? First-of-its-kind sleep clinic launched in Johannesburg

“The quid pro quo is that they be allowed to advertise,” says a faintly apologetic Venter.

The Sleep Clinic also houses a new obesity clinic, where Venter sees patients with South Africa’s new pandemic.

“The new drugs for obesity are every bit as revolutionary as the HIV drugs,” he says, “but every bit as fiddly as antiretrovirals were in 2000”.

New studies, using these wonder drugs in people with both HIV and obesity, are being hatched here to try to improve primary care for diabetes, hypertension and other common diseases in South Africa.

The race to the bottom

The transit away from the streets into cushy offices is one that many organisations working on HIV have made in recent years.

“It is nice not to have to worry about staff being pistol-whipped while at work,” remarks Venter, but donor funding, while key to the fight against HIV in South Africa, has also distanced organisations from communities, and created a dependency which, following the collapse of the US government’s Aids fund, Pepfar, and the United States International Agency for International Development, USAID, threatens catastrophe.

READ | How the health department will deal with Pepfar's near collapse

“What happened still feels quite unthinkable. It is extremely frustrating that our systems have not been made sustainable and are now on the brink of collapse as a result of Pepfar having been interwoven with the national HIV programme to such an extent everything unravels when it is stopped.”

Venter sketches a scenario, in which South Africa’s HIV response – “the one effective programme we have” – is misleadingly characterised as “too expensive”, and dragged down to the lowest common denominator, “leading to the same terrible outcomes you find in crap programmes, like diabetes”.

“A race to the bottom, in other words,” says Venter.

“We have poor indicators for almost every health metric outside of HIV, TB and vaccines, and even those are now slipping, due to the health department dropping the ball.

“Both our public and private health services are an expensive mess, for very different reasons. The health minister has been in charge for most of the last 17 years, we have endless excellent white papers and policy documents that gather dust, and little to show for the continent’s most expensive health system.”

Will this grim scenario prevail, or will South African healthcare be shepherded through the labyrinth of budget cuts and misfiring systems? Venter doesn’t see why not.

Venter says:

Our problems are systemic, and we have enough resources and brains to fix them.

He pauses to mull the judiciousness of his next point.

“I’ll tell you what you do. You take the top people from the medical aids and tell them: You can’t be head of Discovery or the Government Employee Medical Scheme, Gems, anymore, lead with the best people from academia, from government, the private sector, donors, civil society, form a focused group with teeth, and run the health system.

“We all declare our interests, put an end to corruption, and everyone from the president and the minister of health down in government must use the public healthcare system when using their medical aid. If they experience the system first-hand, they will have an immediate investment in assisting those fixing it.

“Start using the innovations South Africans are world leaders in, including data systems. If we do that, I am telling you we will fix the system in five years.”

Venter, clearly, has already rolled up his sleeves for this new fight. It will be interesting to see who joins him.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.

(1).png)

1 month ago

11

1 month ago

11