Image source, Nikki Fox/BBC

Image source, Nikki Fox/BBC

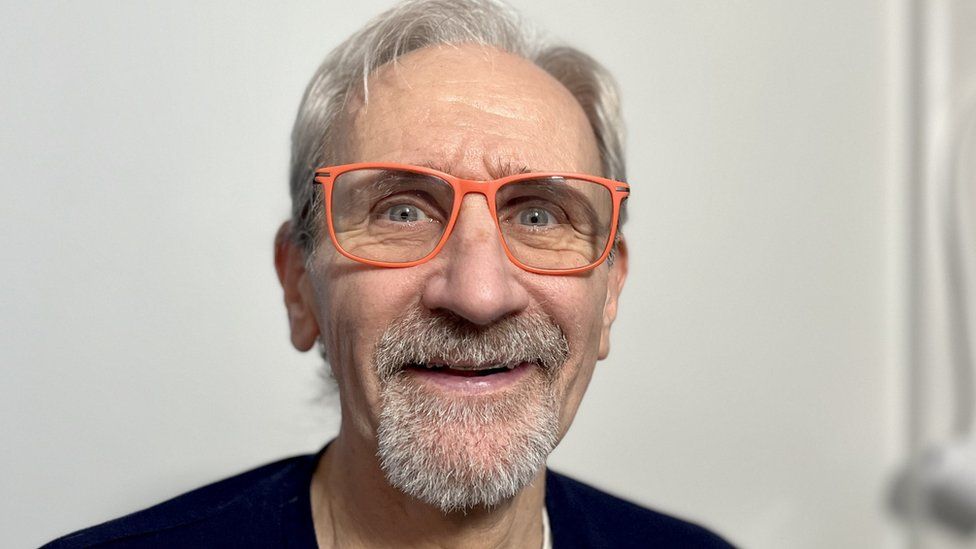

Greg Bright from Norwich signed up to the study before undergoing heart valve surgery at Royal Papworth Hospital

By Nikki Fox

Health Correspondent, BBC East

A plumber has signed as the first recruit to a medical trial using "blood powder" to reduce bleeding during heart surgery.

Patients at Royal Papworth in Cambridge will be given the new "powdered blood product" for blood clots.

Doctors say it could reduce the need for donated blood which is required for around a third of heart operations.

Patient Greg Bright said the trial was a "win win" if it protected "scarce" hospital blood stocks.

The powder is made from a purified plasma protein, a waste product of blood.

It can be stored in the operating theatre - and has a shelf life of two years.

Those who undergo surgery will have their blood tested for thickness, so that patients with thinner blood could be given the product during surgery to prevent bleeding.

Image source, Nikki Fox/BBC

Image caption,The "powdered blood product" is mixed with a saline solution before being given to the patient as an infusion

Royal Papworth Hospital has an international reputation as a centre for heart and lung surgery.

Dr Andy Klein, a cardiothoracic anaesthetist, said the hospital used between 2,000 to 3,000 units of red blood cells during heart surgery each year.

"It really is a big drain on a finite resource," he said.

"We are one of 35 cardiac centres across the country and if you multiply this out to those centres, you could be talking really big savings for the NHS."

About 35,000 people undergo heart surgery in England every year.

Image source, Nikki Fox/BBC

Image caption,Doctors believe the product could save Royal Papworth 3,000 units of blood

Mr Bright, 69, from Norwich, has become the first person to be recruited to the study.

He had surgery to repair a heart valve and said heart issues ran in his family.

He said his mother needed a double heart bypass while his brother had a hole in his heart.

Mr Bright said it was an "honour" and a "privilege" to take part in the trial.

"When they told me it was something that could prevent me from getting a transfusion and that could help other people, I was all in," he said.

At the moment, patients who suffer bleeding during surgery are given donated blood and frozen plasma, which has to be stored in freezers away from the operating theatre.

It can take 45 minutes to thaw out and has to be used within four hours.

Image source, Nikki Fox/BBC

Image caption,Frozen plasma products have to be used within four hours of defrosting and are sometimes wasted as a result

If successful, Dr Klein said the trial had the potential to improve survival rates.

"People who do not need transfusions typically have better outcomes, fewer complications, a shorter length of stay in hospital and quicker recovery," he said.

The study is looking to recruit 620 patients and is being run at 13 hospitals across five countries in Europe.

It is hoped the trial will finish by the end of 2024.

(1).png)

1 year ago

12

1 year ago

12