(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

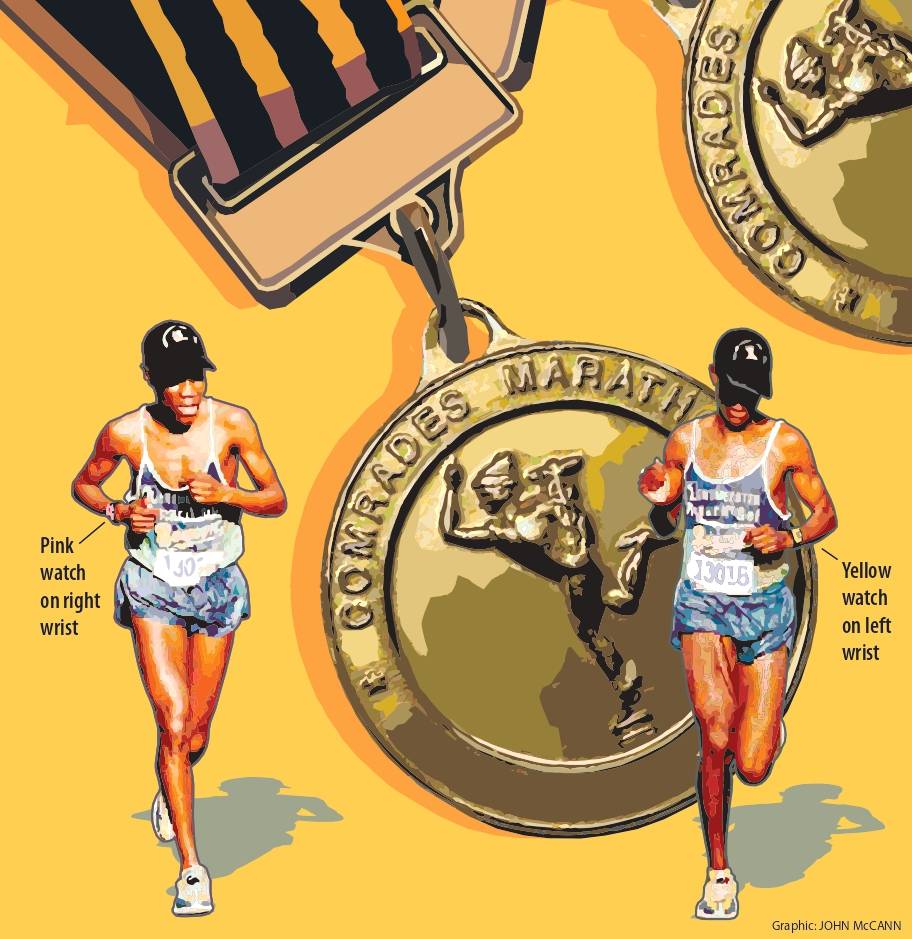

Sergio Motsoeneng, a 21-year-old long-distance champion from Phuthaditjhaba, a poverty-stricken area in the former homeland of QwaQwa, took his place on the Comrades Marathon starting line in Pietermaritzburg on 16 June 1999. His race number, 13 018, was pinned to his vest. He was wearing a black cap, a pair of blue-and-yellow Nikes and a pink watch on his right wrist. (Remember the pink watch.)

The runners sang Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika and Shosholoza, then the Chariots of Fire theme was blasted over the loudspeakers. It’s a rousing tune that has come to represent human endurance and determination. And Sergio had bucketloads of determination. It was his first Comrades but he had won many long-distance races in Phuthaditjhaba and with a competitive marathon time of 2hr 19min under his belt he wanted to see if he could win the world’s oldest and most famous ultramarathon. And not only win it, but break the Comrades record too.

If the lanky runner crossed the line first he would win R100 000. His running club, Rentmeester Reparil Gel, had promised another R1 million for breaking the record. Sergio lived with his 10 brothers and sisters in a two-bedroom house and the family had financial difficulties. With his winnings, he would be able to buy them out of debt.

At 6am, a cock crowed twice (not an actual cock, a recorded cock) and the Pietermaritzburg mayor fired the gun signalling the start of the 74th edition of the Comrades Marathon and sending Sergio and 16 806 other extreme athletes on an 89.9km race to Durban. The fastest would get there in five-and-a-half hours, give or take a minute or two. Most, though, would run, jog, walk, hobble and crawl to the finish in the final 60 minutes before the 11-hour cut-off.

Sergio didn’t break the Comrades record and he didn’t win the race. He finished ninth in 5hr 40min, almost 10 minutes behind the winner, Poland’s Jaroslaw Janicki. Nevertheless, it was a remarkable achievement for a young athlete. Running pundits agreed he had a long and bright career ahead of him.

For finishing in the top 10, Sergio received a coveted gold medal — made with actual gold — and R6 000. Not the R1.1 million windfall he’d wanted, but R6 000 went a long way in 1999. In an interview after the race, he said he would give his gold medal and prize money to his father.

But Nick Bester, an ultramarathon veteran who had won the race three years earlier, smelt a rat. Sergio had beaten Bester, who came 15th, by eight minutes. The timing mat showed Sergio was seven minutes behind Nick at the halfway mark but Nick couldn’t remember Sergio passing him in the second half of the race. He lodged a complaint with the Comrades Marathon Association.

Race officials examined data from the computer timing system but couldn’t see anything out of the ordinary and Sergio was cleared of cheating. The young athlete returned to a hero’s welcome in Phuthaditjhaba and all was well until photos were published in Beeld newspaper a few weeks later.

Now is the time to remember the pink watch. One photo snapped in the first half of the race showed runner 13 018 with a pink watch on his right wrist, while another from later in the race showed the same runner with a yellow watch on his left wrist. This was Bester’s gotcha moment, the point in the whodunnit where the sleuth works out how the murder was committed.

A closer look at the photos also revealed that Sergio had grown a scar on his left shin during the race. You see, it wasn’t the same runner. The man in the first photo was Sergio’s brother, Arnold. Sergio is two years older than Arnold but the brothers have an uncanny resemblance and had often been mistaken for each other.

Confronted with the mounting evidence, the brothers confessed to working out a complicated bait-and-switch operation. It’s still not clear how many times they traded places. One report claimed they switched once at the halfway mark but another said they ran a relay and swapped places several times.

The exchange (or exchanges) took place in a mobile loo (or mobile loos) where the brothers hurriedly swapped their clothes, caps, shoes with timing chip attached to the lace, everything — except their watches. Sergio then ran to the finish.

Caught out, Sergio handed back his prize money and medal and the brothers were banned from the sport for five years.

“If it wasn’t for the fact that he made a mistake with the watches, he probably would have got away with it,” said Cheryl Winn from the Comrades Marathon Association. “That’s really scary.”

Sergio’s lawyer, Clem Harrington, described it as a tragic story. “Hopefully, Sergio will not be lost to the sport because he is a highly talented runner. If he harnessed the energy he put into cheating into rather running the race properly, who knows, he might finish in the top five,” he said.

After serving his ban, Sergio returned to the Comrades and had a string of impressive runs until he proved Harrington right in 2010 and came third, winning another gold medal and R90 000. “It just goes to show he did not have to do what he did in 1999,” said Winn. “He has great ability.”

Unfortunately, his triumph was short-lived. Six weeks later, Sergio was found to have cheated once again, this time testing positive for the performance-enhancing steroid nandrolone. He received a two-year ban and had to forfeit his prize money and his gold medal for a second time.

But despite the twin controversies, Sergio wasn’t done with the gruelling marathon. In 2019, on the 20th anniversary of the ill-fated bait-and-switch Comrades, Sergio, now 40, lined up in Durban. He sang Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika and Shosholoza, listened to the Chariots of Fire theme and the double cock-crow and made his way to Pietermaritzburg in 7hr 21min.

Bullshit: 50 Fibs That Made South Africa is from Jonathan Ball.

And he isn’t the only sport star caught peddling bullshit …

Hansie Cronje remains South Africa’s most infamous sporting cheat but the country has produced several others.

Kevin Evans and David George were mountain biking rock stars — they appeared on magazine covers, had groupies and were the heroes in An Epic Tale, a documentary about their crusade to be the first South African team to win the Cape Epic. But the dream came to a shuddering halt in 2012 when George tested positive for doping.

In what might be a cycling first, he didn’t try to shift the blame (“My ex-wife sabotaged me”, “I ate contaminated meat” or “Having sex before the test caused a testosterone spike” are all actual excuses which have been given). George admitted guilt and was banned for two years.

In 2016, the South African Institute for Drug-Free Sport found irregularities in Evans’s biological passport and banned him for three years.

When journalist Thomas Kwenaite covered an under-15 tournament in France in 1998, he discovered — and reported — that the captain of South Africa’s winning side was an engineering student in his early 20s. The player’s father took Kwenaite to the press ombud for “slander” but withdrew his complaint when Kwenaite produced records to show that if the player was under 15, he would have been two years old in grade one.

Ronel Liss caused a kerfuffle at the 2002 edition of the Cape Argus Pick n Pay Cycle Tour (now the Cape Town Cycle Tour) when she told officials she was the true winner of the women’s race.

Moments after Anriette Schoeman lifted the trophy, Liss, who had no track record as a competitive cyclist, insisted she had crossed the line 15 seconds before her. And her husband Jago had proof.

The ceremony was stopped and Schoeman’s celebrations were put on ice while officials investigated. They decided to examine Jago’s result as well.

Fallen star: Cyclist Kevin Evans, hero of the documentary An Epic Tale, was banned for doping. Photo: Chris Hitchcock / Gallo Images

Fallen star: Cyclist Kevin Evans, hero of the documentary An Epic Tale, was banned for doping. Photo: Chris Hitchcock / Gallo ImagesHe had “won” the men’s A category — the top amateur group — by an unheard of 18-minute margin. Turns out that the Lisses had taken some shortcuts and both of them were disqualified.

Esports have become hugely popular, with technology allowing cyclists to race against riders from all over the world while sitting on stationary bikes in the comfort of their homes.

This is what East London virtual cyclist Eddy Hoole did in December 2022 when he competed in a UCI Cycling Esports World Championships qualifying race. Fans watched in disbelief as Hoole’s avatar broke away from the peloton and flew up a hill to win.

When officials crunched his data, they found Hoole had generated significantly more power than Olympic champions. It was soon discovered the software developer had hacked the data.

Cycling South Africa found him guilty of cheating and suspended him from all cycling disciplines for six months. — Jonathan Ancer

(1).png)

7 months ago

87

7 months ago

87