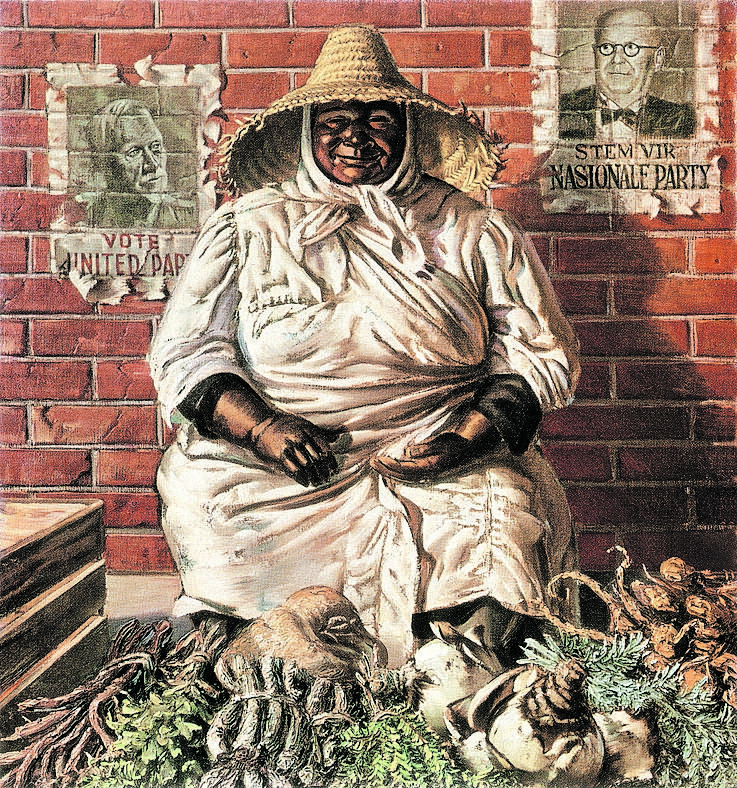

Museum grade: Vladimir Tretchikoff’s 1949 painting Herb Seller was his first painting to be exhibited in the South African National Gallery, in 2010.

In a few weeks’ time, two major auction houses — Strauss & Co in Cape Town and Bonhams in London — will be selling high-value paintings by Vladimir Tretchikoff, the vertigo-inducing merchant of kitsch.

For those prone to nausea at the sight of Tretchi’s potboilers, now is a good time to stockpile ginger, a known anti-emetic .

Given the resilient market for a major Tretchi, especially since the 2013 acquisition of his Chinese Girl (1952) for R13.8 million at Bonhams, there is every possibility that bidding will be energetic at both auctions.

But what exactly constitutes a major Tretchi? The two high-value works up for grabs this month suggest an answer.

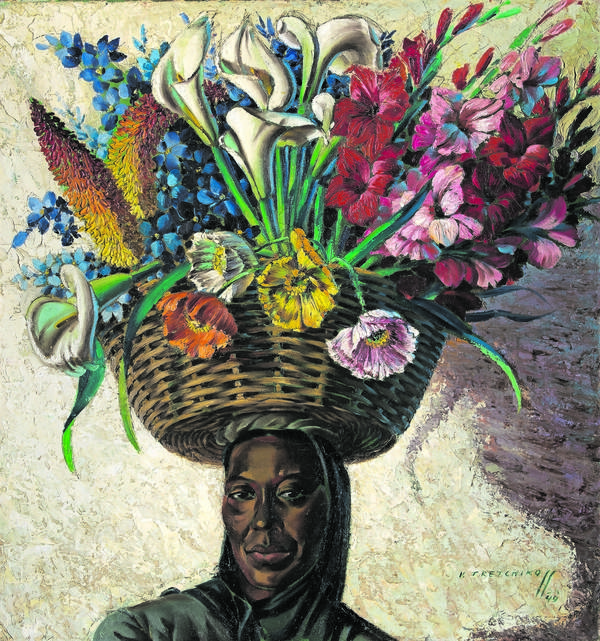

On 19 March, Strauss & Co will offer Tretchi’s Flower Seller (1949). The painting depicts a Cape Muslim woman bearing a wicker basket on her head, loaded with an abundance of cut flowers, including red-hot pokers, arum lilies and gladioli.

Cape Muslims were already a stock subject among white painters by the time Tretchi — a wandering Russian émigré who settled in Cape Town in 1946 after time spent in China, Singapore and Indonesia — made this work.

A skilled illustrator with an unrestrained affection for vivid colour, Tretchi’s quasi-naturalistic paintings of settled genre subjects annoyed local Cape artists and critics alike.

Irma Stern famously engineered the retraction of an offer to Tretchi to show in a prominent gallery. Undeterred, Tretchi exhibited his work in a nearby department store. His show was a hit.

Much in the way that Instagram allowed artists to “hack” the sedentary art market circa 2020, Tretchi found alternative routes to connecting with audiences. He showed in department stores, including Harrods in London, and made print reproductions of his paintings.

Tretchi’s robust trade sponsored an equally vibrant industry of insults.

“His world is blatant, cheap, unfeeling, but, oh, so mechanically striking,” wrote one critic in the Afrikaans Cape newspaper Die Burger in 1949.

Three years later, The Cape Times accused him of “lachrymose sentimentality”, which is fancy speak for saying his paintings were unsophisticated hackwork — in a word, kitsch.

Brainy critics were greatly preoccupied by mass culture and kitsch circa the beginning of the last century.

“Kitsch is mechanical and operates by formulas,” wrote American critic Clement Greenberg in a landmark 1939 essay on kitsch characterised by its Talmudic gravitas.

“Kitsch is vicarious experience and faked sensations … Kitsch is the epitome of all that is spurious in the life of our times.

“Kitsch pretends to demand nothing of its customers except their money — not even their time.”

Tretchi, a quintessential poptart, embraced this new ersatz culture. His mass-produced prints operated like memes.

Frank Kilbourn, chairperson of Strauss & Co, says the wide distribution of Tretchi’s prints in urban and rural communities created a “huge awareness” of his works.

Kilbourn, an avid art collector who was brought up in a rural farming community in the North West, experienced this first hand.

“We grew up with him in the house. He was also quite a character and his wealth and fame supported the interest in his work.”

Tretchi’s pluck and flamboyance inflamed the passions of critics. Far more damaging than the bon mots and putdowns of critics, especially for a try-hard like Tretchi, was the unofficial edict against showing his work by successive directors of the South African National Gallery in Cape Town.

Riason Naidoo broke with this “existentially displaced Eurocentrism”, as critic Ashraf Jamal labelled it, when he became director in 2009.

Naidoo included Tretchi’s Herb Seller (1949), a portrait of a well-known trader on Cape Town’s Grand Parade, in his survey exhibition 1910-2010: From Pierneef to Gugulective.

A year later, Tretchi received a full-blown survey in the museum.

The marketing for this exhibition yielded a dubious new nickname for the tsar of treacle — Tretchi was rebranded as “the people’s painter”.

Strauss & Co’s Flower Seller (1949) dates from the same year Tretchi painted Herb Seller. It is expected to sell for between R1.8 million and R2.4 million.

This is half the value Tretchi’s Lost Orchid (1948) is expected to fetch when it goes on sale in London on 27 March.

Lost Orchid depicts the remnants of a party on a staircase, including streamers, a spent cigarette and a floral corsage, its orchid dripping moisture like tears.

I suppose it could charitably be interpreted as a memento mori painting, where the fleetingness of life and inevitability of death is narrated through objects. But it also exemplifies the artist’s fond indulgence in cheap sentiment.

“Tretchikoff is popular and collectable because his works have a strong visual identity that is usually combined with his noted sentimentality,” says Giles Peppiatt, group head of fine art at Bonhams.

“Collectors do find this highly appealing. It is also helpful that the prices achieved for the major works hold up well and that the market is strong for these paintings.

“When it comes to the three Ps of collecting — passion, profit and prestige — Tretchikoff seems to tick all the boxes.”

Lost Orchid is one of the crown jewels in Tretchi’s catalogue of sentimental errors. It has been extensively reproduced. It also comes with a cute provenance.

John Schlesinger, the young heir of IW Schlesinger’s sprawling South African business empire, was the first owner of Lost Orchid.

Now remembered as an important art collector, Johnny Schlesinger, as he was known for a while, had a reputation as a privileged wastrel around the time he acquired the work for his wife.

Time magazine in 1963 characterised Schlesinger as “a Harvard-educated playboy with plenty of hustle in a speedboat race and a keen eye for judging beauty queens”.

Tretchi loaned the painting back from Schlesinger to tour abroad. Starting in1952, Lost Orchid travelled throughout the US. At a stopover in Chicago it caught the eye of journeyman actor Mark Dawson. He made enquiries. Too expensive, he learnt and, anyway, sold.

A business artist before Andy Warhol coined the term in 1975, Tretchi bought Lost Orchid back from Schlesinger at three times the original purchase price. In 1955, he sold it to Dawson, whose descendants are now selling the work.

Tretchi painted numerous works that are a variation on a particular theme. Many painters do this.

Tretchi’s distinction lay in his habit for excavating cheap sentiment. Fallen flowers abound in his work.

FL Alexander, an important mid-century critic, was so exasperated by Tretchi that he refused to name the artist in his press writings, referring to him simply as “The Master of the Fallen Flower”.

One fallen flower should not be mistaken for another, as a curious incident from recent history reminds.

After the 2005 murder of Brett Kebble, a disgraced empowerment impresario and art collector, his vast estate was liquidated at various public auctions.

In 2009, Johannesburg dealer Graham Britz mistakenly offered a work closely resembling Lost Orchid in a much-publicised sale of Kebble’s art collection at Summer Place in Johannesburg.

Thinking it was the work once owned by Schlesinger, mining entrepreneur Anton Taljaard made the winning bid. Except it wasn’t that work. When the painting was examined against a reproduction appearing in a book, it was seen to be missing one of the dewy drops of sentiment on the orchid.

Other minor discrepancies were noted. Cue much hand-wringing and expensive research.

Vladimir Tretchikoff’s Lost Orchid.

Vladimir Tretchikoff’s Lost Orchid.A year later, it was revealed that a cataloguer for Britz had ignored Tretchi’s original title, written on the back of the work. After the Party, for which Kebble had paid R16 000, had somehow become Lost Orchid. Oops. The sale was rescinded.

The provenance of Lost Orchid and After the Party highlights an enduring truth about Tretchi — he might be the people’s painter but he also appeals to the rich and powerful.

I asked Bonhams’s Peppiatt about Tretchi’s collector base.

Is it limited to wealthy South Africans or is it more geographically scattered and diverse?

“The collectors for the major works by Tretchikoff come from across the globe,” replies Peppiatt.

“This is the important distinction as it is only the finest works that attract international buyers.”

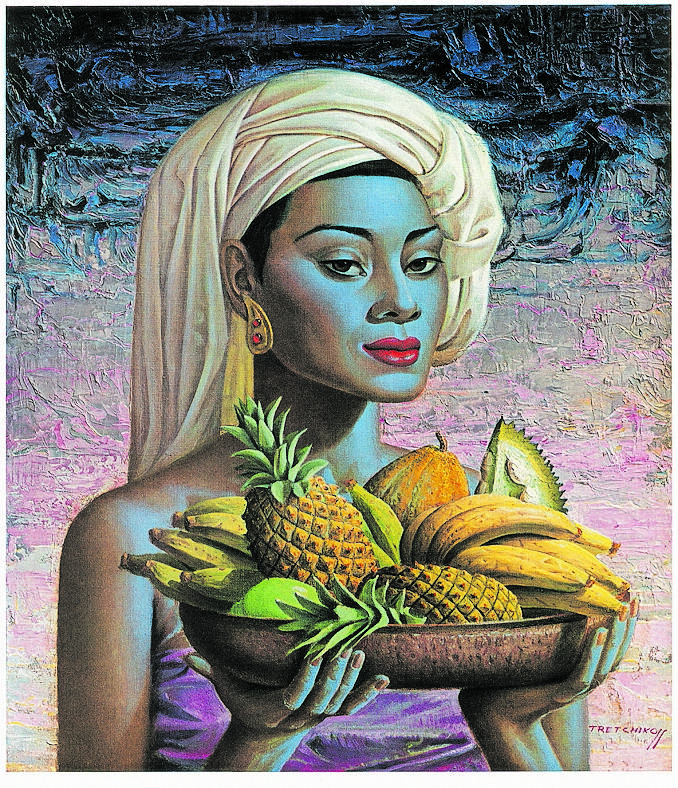

He offers Chinese Girl, a portrait of Sea Point, Cape Town, resident Monika Sing-Lee, as an example.

When it went on sale in London in 2013, says Peppiatt, many non-South African bidders chased after it. British gem dealer Laurence Graff came out the winner.

Chinese Girl was shortly unveiled at the Delaire Graff Estate in Stellenbosch.

Tretchi’s work Fruits of Bali (1960), which was sold for R4.7 million in London in 2019, was purchased by an international collector with no link to South Africa.

“So, there are two distinct markets: the lesser works that generally appeal to domestic South African buyers and the major works that have an international appeal,” Peppiatt says.

The enduring appeal of Tretchi’s major paintings suggests that this merchant of kitsch is ultimately enjoying the last laugh.

But for Irma Stern, and possibly Gerard Sekoto, whose works occasionally appear on international auctions, no South African modernists have made the jump from national hero to internationally collectable artist.

I always thought the essential question to ask of Tretchi was, “How can such mediocrity sell?” Time to eat humble pie.

The question circa 2024 is this, “How much more runway is there left for such mediocrity?” By some accounts,a great deal.

Auctions later this month will reveal more.

(1).png)

9 months ago

34

9 months ago

34