Juggling act: Polls and predictions are that the ANC is wobbly and during these elections – and after – will need all the help it can get. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

NEWS ANALYSIS

The ANC is likely to lose its majority in the National Assembly after the 29 May poll.

Parliament, once a theatrical disguise for the true centre of power at Luthuli House, will suddenly be thrust back into the limelight.

What then? To a large extent, the future will be determined by how far the ANC slips below 50%.

The lower the better, opposition parties would have it. But the lower the wobblier, “the markets” might say.

The further the ANC slips below 50%, the more permutations are on the table in the scramble to form a multi-party government. And, of course, the more vulnerable the president to the whims of change always lurking in the ANC, waiting for any sign of weakness.

So, yes, finally, change may be upon South Africa. But will the grass be any greener on the other side?

In the 2021 local government election, the ANC fell to just 45.6% of the ward and proportional representation vote. While local government elections are not always a perfect predictor of general elections results, because of the unique factors and local parties involved, it constitutes the most recent authoritative poll of the South African electorate.

Since then, the situation has not improved electorally for the ANC and the emergence of uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) party seems to have put pay to its hopes of winning more than 50% of the vote.

While the MK party is also eating the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and Inkatha Freedom Party’s (IFP’s) lunch as much as that of the ANC, it is likely to swallow a few percentage points that the ANC could ill afford to lose.

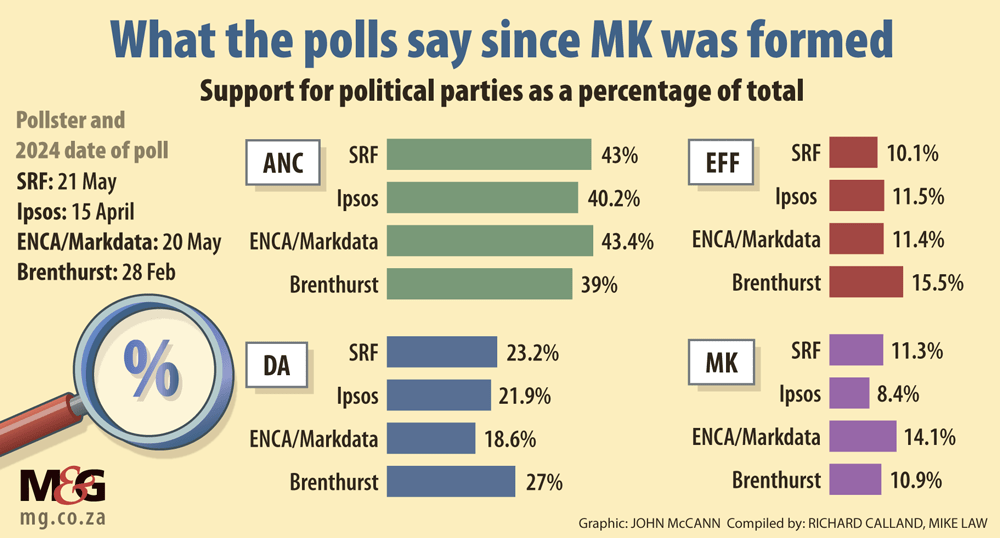

Since the emergence of the MK party, opinion polling has placed the ANC in the high 30% or low 40% range. South Africa is a notoriously difficult country to poll. Achieving a sufficient and representative sample is an almost impossible task, as is verifying that respondents are indeed registered voters.

The polling numbers don’t look good for the ANC. But, historically, polling in South Africa has tended to understate the ANC’s support, especially when proper turnout modelling is factored in.

As such, our view is that the ANC is more likely to achieve a result of mid-to-high 40%. And a 50% majority still cannot be ruled out.

The precise number that the ANC falls on will be crucial for the story to follow.

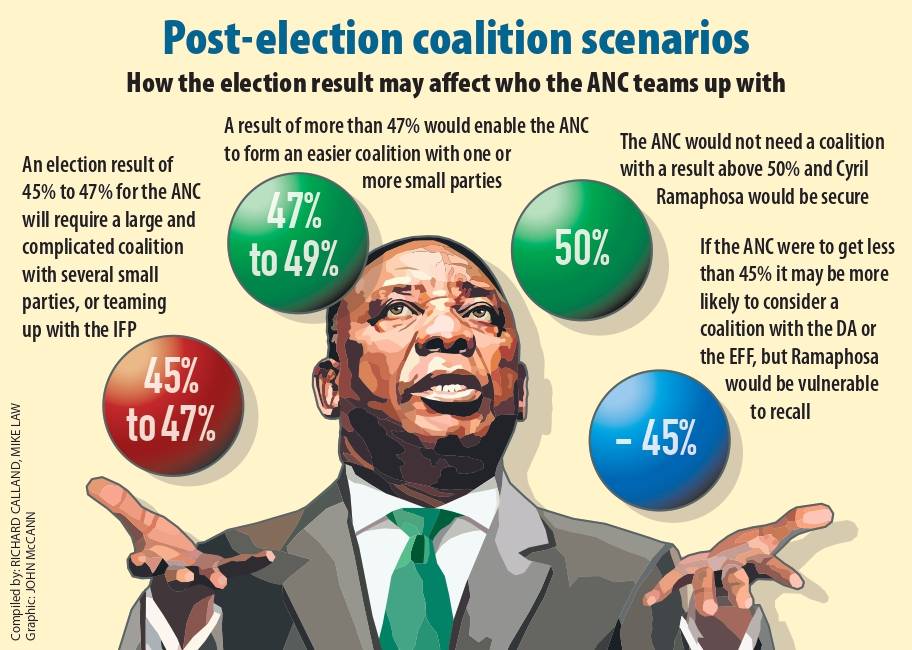

A result of more than 47% will mean the ANC should be able to form a relatively straightforward coalition with one or more smaller parties, resulting in something that is little different from the status quo. Although they may not now admit it, that would probably be an acceptable result from the perspective of the ANC. President Cyril Ramaphosa will be able to claim it as a victory of sorts, especially if the final outcome is higher than the 2021 local government elections result.

A result between 45% and 47% — which we currently hold as our “base case” — makes the situation a bit more complex. A coalition between the ANC and smaller parties may still be possible under this scenario, but it would require a larger coalition between several small parties, making it hard to manage and maintain stability.

Or, the ANC could do a deal with the IFP. The IFP is part of the opposition cohort’s Multi-Party Charter. The IFP’s leader, Velenkosini Hlabisa, has frequently said that it will not do a deal with the ANC.

But, even if the charter really ever was a coherent political “thing”, loyalty in it will be tested and strained as soon as the polls open. Could the IFP yet be enticed into a deal that sees it supporting the ANC in national government, in exchange for the IFP taking the premiership in the KwaZulu-Natal provincial legislature that is now certain to be hung?

We wouldn’t rule that out. Similar story for the Democratic Alliance (DA). Despite its purported dedication to the charter, it has been teeing up the idea to its voters for some time that the party may have to entertain some sort of relationship with the ANC to “protect” South Africans from what they call a doomsday coalition between the ANC and EFF.

But, for the “grand-coalition” option (ANC plus DA) to be explored, something that a fair few in the business community would like to see, our view is that the ANC would have to drop below 45%.

In that scenario, neither the small parties nor the IFP alone would be able to take the ANC above 50%. That would be a proper fork-in-the-road moment for the ANC, pushing it towards a choice between red and blue.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)Which would be the lesser evil, from the ANC’s standpoint?

That depends on a few things. First, of course, whether the DA or EFF are even willing to do a deal with the ANC and, especially in the latter case, if they can put forward terms of cooperation upon which it is possible to agree.

The EFF has tended in the past to overplay its hand in negotiations. But it’s leader, Julius Malema, appears to be going through some kind of strategic reset with his main goal being to be a king-making player in a coalition government. There have been rumours that his price would be the deputy presidency.

Another critical suspensive condition is who the president of the ANC will be in that scenario, or at least which actors in the party are in the strongest position of power. Who, in other words, will be in charge of the ANC side of the negotiations.

Make no mistake, a result in the low 40% for the ANC and Ramaphosa will be vulnerable. Well into his second term as ANC president, and in all likelihood having fought his last national general election in the role, attention and opportunity in the party will pull towards whatever it is that comes next.

So, if it is Deputy President Paul Mashatile’s camp calling the shots in the ANC at that stage, then the red option is more likely. If there is any chance of seeing a working arrangement between the ANC and DA, then it would surely only be with Ramaphosa at the helm of the ANC.

It’s hard to overstate the significance of the decision that the ANC would face in that scenario, a decision that will divide the party to its core, and set its direction of travel for the medium-term future.

In this article, the word “coalition” is used to describe the form of inter-party collaboration it would take to yield a governing majority. But there are other forms of power-sharing, formal and less formal, that could yield the same effect.

For example, there could be a minority government, elected with the voting support of another party to get it to 50%, but without the promise of its enduring loyalty on each and every parliamentary vote.

Whatever the arrangement, it is unlikely to be as clearly expressed and defined as the need for stable governance would require.

That is in large part because of the short period of just 14 days prescribed by the Constitution between the time that the Electoral Commission of South Africa declares the final results to the time that the president must be elected by the National Assembly. This is quite different to countries with a long history of coalition politics, where negotiations can take months.

So, in the event that the ANC does fall below 50%, whichever government emerges in the initial weeks may well be on a rocky footing. Certainly from the experience of coalitions at local level, it should hardly be expected that the arrangement will last a full five-year term.

Instability is likely to characterise the short-term future as South Africa comes to grips with the art of doing coalition politics, absent a legal framework and a mature enough political culture conducive to that purpose.

All nine provinces are governed by a majority, eight by the ANC and one, the Western Cape, by the DA.

That is set to change.

The ANC is certain to lose its majority in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal. The party’s slide in the two largest provinces is set to be hugely damaging for its national result — heaping pressure to return big numbers again in its strongholds of the Eastern Cape and the inland provinces.

Although the numbers still lean slightly to the ANC’s bloc in Gauteng, it is not impossible that a coalition of charter-aligned parties could push the ANC out of the provincial government. In KwaZulu-Natal, where stability is generally the exception, it will be up to the ANC, IFP and MK party to sort it out, although the DA and EFF’s votes will be important in the jostling to form a majority.

The Northern Cape and Free State, where the ANC’s majority is looking increasingly slender, are also set for close races. The North West, too, is not safe for the ANC, although it has more margin there compared with the other provinces. Its majority in the Eastern Cape, Limpopo and Mpumalanga should be safe, but nothing can be too certain in an election that is very hard to predict with so many untested forces, a long ballot paper and fast-moving electoral sentiment.

And then, in the Western Cape, the DA’s majority is not safe either.

The DA’s meteoric rise from single digits in the province in the 1990s peaked at 63.3% in 2016 when Patricia de Lille was running for mayor of Cape Town.

Since then, the DA has been on a slow decline — 55.5% in the last provincial election in 2019, and 54.2% in the 2021 local government election.

Since then, the Patriotic Alliance, in particular, has shown signs of exponential growth among working-class coloured voters — a crucial constituency for the DA to keep if it is to hold its provincial majority.

So, the Western Cape is also set to be a hotly contested race. But if the DA were to slip just below 50%, it should have the partners that it needs in the provincial legislature to form a relatively friendly coalition.

This election also brings into play parliament’s somewhat forgotten second house: the National Council of Provinces (NCOP).

The NCOP has 90 seats, 10 for each province, allocated broadly proportionally to the provincial vote in each province.

It favours larger parties and parties that do well in smaller provinces. By our modelling, even if the ANC loses its majority in the National Assembly by a few percentage points, it may well still keep its majority in the NCOP.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)What to make of it all?

This is a very difficult election to predict, with a lot of moving parts. In many respects, South Africa is taking a step into the unknown.

The extreme scenarios — that the ANC achieves a result in the low 40% on one hand or, on the other, still manages to scrape a majority — can still not fully be ruled out.

Much depends, as always, on turnout on election day. Which party has got their voters registered and then got the greatest proportion of them to actually turn up at the ballot booth?

Can the MK party live up its to its polling numbers, or was it just a smokescreen masquerading as support? What of Rise Mzansi, on whom no real data is available, but anecdotally at least seems to be capturing the minds of the so-called chattering class? Can ActionSA, in its first national election, replicate the support it won in little over a handful of municipalities that it decided to contest in its 2021 debut?

The performance of these newer parties may be critical in the final shakeup.

While the ANC is set to decline significantly on its 2019 result, that vote is not going anywhere in particular — being split up between a increasingly competitive and fractured party-political playing field. The market becomes ever more congested as newcomers and independent candidates seek to take advantage of South Africa’s extremely low electoral thresholds.

This is an election that provides an opportunity for something new, something better, but it could also deliver something worse. Or, also very possibly, a combination of both, as governing arrangements and coalitions shift back and forth over a turbulent five-year period. A second transition of sorts, or at least the start of it.

Five years from now, South African politics could look entirely different as a new consensus starts to emerge on the other side.

Richard Calland is a visiting adjunct professor at Wits School of Governance and a founding partner at political risk consultancy, The Paternoster Group, where Mike Law is the senior researcher.

(1).png)

7 months ago

58

7 months ago

58