Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov is believed to be sheltering two men linked to plots to assassinate two Uzbekistani officials last year, according to an Uzbek source personally familiar with the situation who spoke to The Moscow Times on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal.

The potential link between the oppressive Russian republic and power struggles in Tashkent could be a sign of the Kadyrov regime’s global footprint expanding into Central Asia, after critics of the Grozny regime have been targeted in Europe and Turkey.

Competition between Uzbekistan’s elites erupted into the open on Oct. 26, 2024 — the day before parliamentary elections — when shots were fired at a car carrying Komil Allamjonov, a prominent political figure with close ties to the presidential family, outside his home near Tashkent.

Komil Allamjonov, the former press secretary to President Shavkat Mirziyoev.

Dilmurod Abdukadyrov (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Komil Allamjonov, the former press secretary to President Shavkat Mirziyoev.

Dilmurod Abdukadyrov (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Allamjonov, who survived the attack, had recently stepped down as head of the Presidential Information Policy Department, citing a desire to return to the private sector.

Despite limited reforms since 2017, Uzbekistan remains a secretive country, meaning there is very little information in the public domain about the attack. Local media are forbidden from reporting anything that has not been released through official channels.

The trial of a “large number of defendants” apprehended by the authorities over the assassination attempt is being held in a military court to make sure nothing that could damage President Shavkat Mirziyoyev or his family gets out.

But Uzbekistan’s placement of two Chechens on Interpol’s wanted list on suspecion of involvement in the assassination attempt prompted outrage from Kadyrov.

The Chechen Connection

The day after the assassination attempt, two men released a video in which they announced they were the gunmen and were handing themselves in to the police.

“We’ve done this only for the money. There are people who promised us money for this,” one of the men says in the video.

Radio Free Europe’s Uzbek service Radio Ozodlik identified the men as Uzbek citizens Shokhrukh Ahmedov and Ismoil Jahongirov.

In 2021, Ahmedov was imprisoned in Turkey alongside four Chechens and another Uzbek native for seven months for participating in a plot to kill a dissident Chechen field commander who was living in the country after fighting with the Syrian opposition.

Turkish media attributed the men’s early release to a personal intervention by Kadyrov, who made an unofficial visit to Istanbul shortly after the group was arrested.

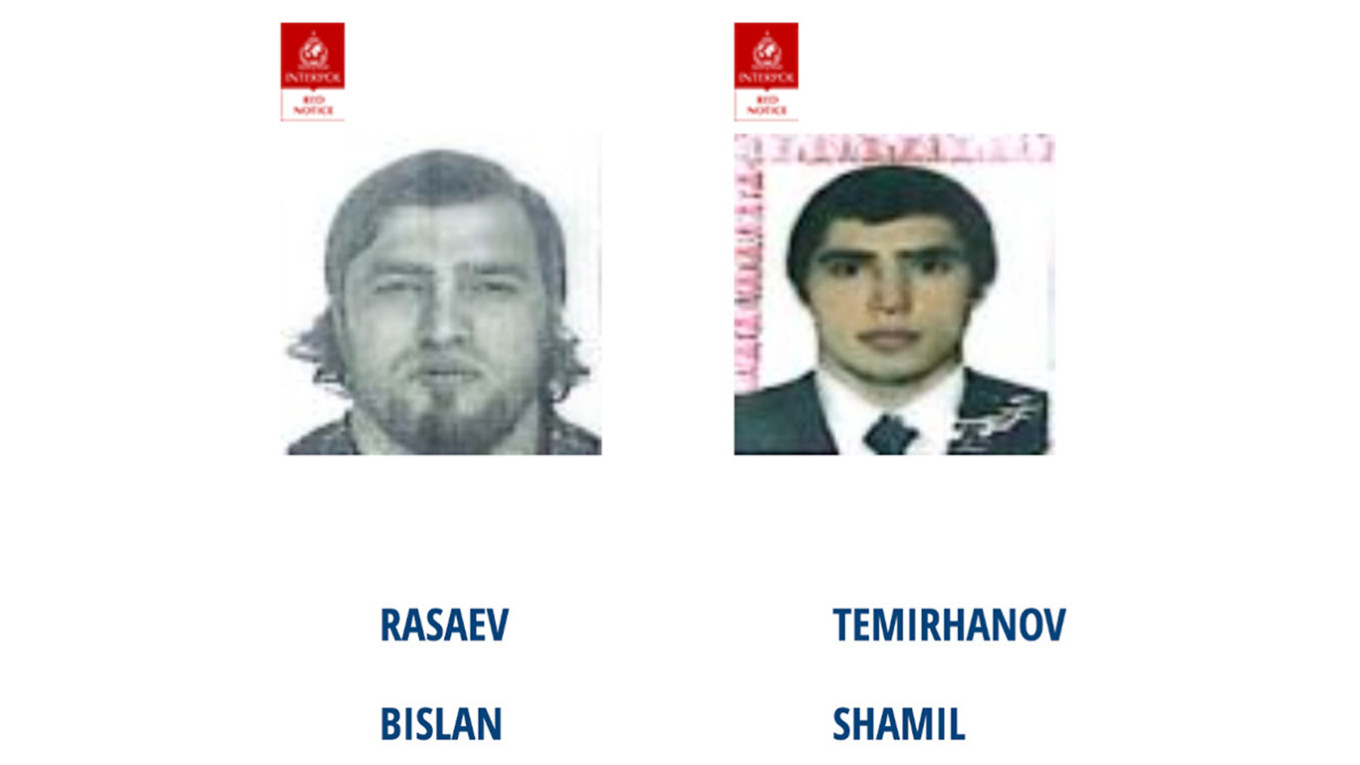

Interpol placed on its wanted list two Chechens suspected of involvement in the plot against Allamjonov and a second alleged attempt on Dmitry Li, who heads Uzbekistan’s gambling and cryptocurrency regulator.

The two suspects on Interpol's wanted list.

INTERPOL

The two suspects on Interpol's wanted list.

INTERPOL

One of the men wanted by Interpol – Bislan Rasayev – shares a name with the leader of the 2021 plot, who reportedly acted on orders from Russian State Duma Deputy Adam Delikhanov, a relative and close ally of Kadyrov.

There has been no official confirmation that the two Bislan Rasayevs are the same person. But two different facial-recognition software used by The Moscow Times to compare the photos released by Interpol in 2024 and Turkish media in 2022 found an 84.14-98.96% chance they were the same person.

After the Interpol notices were released, Kadyrov took to Telegram to deny any involvement in the failed assassination of Allamjonov.

“If I had prepared it, I would have finished the job on the same day,” he wrote on Dec. 26. “You shouldn’t have such a bad opinion of me.”

He accused “pseudo-independent” media of trying to destabilize Uzbekistan’s government and threatened to respond to “intrigues, slander and lies” about Chechen involvement “according to Chechen traditions,” which is understood to mean a blood feud.

Though Tashkent has not commented on Kadyrov’s statement, several officials have. Odiljon Tojiyev, a deputy in the Oliy Majlis legislative chamber, called on Kadyrov to apologize to the people of Uzbekistan and extradite Rasayev and Temirkhanov.

He also called on Russia’s Prosecutor General to assess Kadyrov’s threats against Uzbek officials, which a former deputy described as “terrorism,” calling for flights from Grozny to be suspended and Chechens to be subject to strict checks upon entering Uzbekistan.

Despite Uzbekistan officially remaining neutral on the war in Ukraine and provocative statements from Russian officials urging investigations into the treatment of Russian language speakers, Tashkent and Moscow have continued close economic cooperation.

But Kadyrov’s statement is different.

“Normally, comments from Russian officials reflect Russia’s foreign policy,” Temur Umarov, an analyst at the Carnegie Center, told The Moscow Times. “I don’t remember any other Russian politician involving himself so heavily with something that has nothing to do with Russia.”

Independent analyst Harold Chambers told The Moscow Times that Kadyrov sees himself as having a special tie to Uzbekistan through his father Akhmat, who studied at Islamic schools in the country, as well as personal economic investments.

“While Tashkent will surely seek to elevate its pressure to extradite the suspects, Kadyrov is unlikely to hand over Rasayev,” Chambers said. “Extraditing regime-tied assassins is something Kadyrov would have to be strongly pressured or substantially incentivized to do.”

Moscow has not publicly commented on the situation.

“President Putin and President Mirziyoyev maintain a very good personal relationship. All foreign policy decisions in Russia are made by Putin. Kadyrov heads one of Russia's regions, and this does not fall within his authority,” source close to the Kremlin told The Moscow Times. “However, he does have a certain degree of autonomy and an unofficial mandate from the Russian president to maintain relations with some Islamic states on issues related to Chechnya’s regional agenda,” the source continued.

A Tashkent Power Struggle

The 2016 death of Islam Karimov, who ruled Uzbekistan with an iron fist since the disintegration of the Soviet Union, saw some of the country’s restrictive policies relaxed. The economy opened up to foreign investment — largely from China and Russia — and relaxed visa policies in a push to draw international tourists to its ancient Silk Road cities. This new openness created opportunities for Uzbekistan’s elites to jostle for power.

Uzbekistan’s tentative steps out of the Karimov era were met with opposition from the country’s powerful security services. Despite economic and social reforms including closing a notorious prison camp and ending the systematic use of forced and child labor in the cotton harvest, Uzbekistan remains a “consolidated authoritarian regime,” according to Freedom House. A 2023 referendum allowed Mirziyoyev to stay in power until 2024 and many of his family members hold powerful positions in the government and business.

Allamjonov, who was brought in from the private sector to manage the government’s image and communications, spearheaded a slight softening of Uzbekistan’s media landscape.

His office unblocked the websites of independent outlets including the BBC’s Uzbek service, Eurasianet, Fergana News and Human Rights Watch. He sat for an interview with Radio Ozodlik and allowed its journalists to get short-term accreditation, though access to the website remains restricted. His job as the head of the presidential Information Policy Department made him the third most powerful person in the administration.

He is also a close ally and political mentor of Saida Mirziyoyeva, Mirziyoyev’s eldest daughter who some Uzbekistan watchers see as a potential successor to her father. Poised and media-savvy, she has served as first assistant to the president since August 2023, the second-highest-ranking position in the country. Experts suggested that the attack on Allamjonov could be an attempt to weaken her position in a struggle for power.

Mirziyoyeva is not the only member of her father’s family to hold office. Her brother-in-law, Otabek Umarov, was the deputy head of the presidential security service and reportedly had a “poisonous” relationship with Allamjonov.

This antipathy escalated after Umarov suspected Allamjonov of blocking the work of an unofficial organization Umarov used to carry out “mob-style shakedowns” of businessmen and politicians.

A source provided evidence to The Diplomat that this organization — “the office” — tried to discredit Allamjonov and Li, including spreading rumors and trying to get them added to the U.S. sanctions list. When they failed, the source said an attempt was made to assassinate Allamjonov.

The Moscow Times approached Umarov for comment through the National Olympic Committee of Uzbekistan, of which he is vice president, but did not receive a response.

“The office” is also reported to have pressured bloggers and journalists to spread the rumor that Allamjonov staged the attempt on his own life. The claim also appeared on a pro-war Russian Telegram channel and was amplified by the popular Rybar account, which claimed Allamjonov was backed by the West to discredit the most actively pro-Russian figures in Uzbekistan’s government.

Umarov is also connected to one of the men detained in the assassination probe, Javlon Yunusov, through a friendship between their wives. Yunusov was extradited from South Korea at Tashkent’s request and reportedly employed one of the gunmen as a driver and bodyguard.

Following the botched attack, Mirziyoyev fired the heads of the State Security Service (SSS) and the Presidential Personal Security Service. Otabek Umarov was reportedly dismissed from his role at the SSS in late November, but there has been no official confirmation.

Carnegie’s Temur Umarov — who is unrelated to Otabek Umarov — told The Moscow Times the president fired them so he could be seen to take action without damaging his family’s position.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Continue

![]()

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

(1).png)

2 days ago

4

2 days ago

4